Sid McNally joined Essex County Fire and Rescue Service in January 1995. In 2012, when he was 48, his wife noticed a lump on his neck and insisted he go to his GP, who referred him to the hospital.

The hospital took a biopsy of his neck and decided to remove the lump. After surgery, he was diagnosed with cancer of the base of the tongue. The consultant asked how many cigarettes he smoked per day. He had never smoked.

Sid (centre) recovered. But not all are so lucky, and the cancer risk faced by firefighters is worryingly high.

This is the conclusion of a University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) independent report, commissioned by the Fire Brigades Union (FBU) and described as a ‘UK first’.

Commenting on its findings, FBU general secretary Matt Wrack said: “Firefighters risk their lives every day to keep their communities safe. But it’s clear that the risk to their health doesn’t stop when the fire has been extinguished. Sadly we often see serving and former firefighters suffer from cancer and other illnesses.”

Where there’s fire

UCLan’s report includes a summary of over 10,000 responses to a national survey of currently-serving firefighters run jointly with FBU. It indicates working firefighters are diagnosed with cancer at four times the expected rate, with 4.1 per cent of firefighter respondents affected. Threequarters had served for at least 10 years before receiving their diagnosis; more than half were under the age of 50 and a fifth were under 40.

Of those diagnosed, 26 per cent had been diagnosed with skin cancer, followed by testicular cancer (10 per cent), head and neck cancer (4 per cent) and Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (3 per cent).

Before treating Sid, his consultant had already diagnosed one of his colleagues, Steve, with the same cancer. Steve, also a non-smoker, died several years later.

“I feel I was lucky as my cancer was identified at an early stage. With chemo and radiotherapy treatment, I managed to return to work in just over six months,” Sid said. “Sadly my mate Steve, who I’d served with on the same watch for three years, did not survive.”

Exposed by design

Fires produce a cocktail of toxic, irritant and carcinogenic chemicals in the form of aerosols, dusts, fibres, smoke, fumes, gases and vapours. On-site workplace testing by UCLan at 18 fire stations and training centres found exposure to carcinogens – cancer-causing substances – is still routine, in both call outs and training.

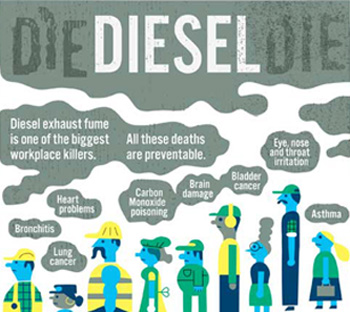

DIESEL DEATHS Professional drivers are facing a routine and serious health risk from diesel exhaust fume exposures at work, a UK study has found, with drivers working for the emergency services in the high risk group. more

Indoor air testing revealed firefighters are exposed to high levels of toxic contaminants during and after a fire, as cancer-causing chemicals remain on PPE, clothing, equipment, and elsewhere at the fire ground. Test samples identified carcinogens inside firefighters’ helmets, on PPE, and on breathing apparatus mask filters.

Half of the survey respondents did not think their fire service took decontamination practices, including cleaning PPE and equipment, seriously. And while UK law requires firefighters’ PPE to meet heat-resistance, heat transfer, and water resistance requirements, it is not required to protect wearers from toxic gases and particulates.

Cancer consequence

In almost all states in the USA and provinces in Canada, compensation laws presume certain cancers in firefighters to be occupational diseases. These ‘presumptive’ laws typically cover brain, bladder, ureter, kidney, colorectal, oesophageal, breast, testicular, prostate, lung and skin cancers and leukaemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

In 2018, the Canadian province of Ontario added cervical, ovarian and penile cancers to its list.

So far, the UK is refusing to follow suit. “This means that, if a firefighter believes their illness is work-related, they are required to prove it – an almost impossible retroactive task,” FBU notes.

There is a solution. A July 2019 report from the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee recommended: “The government should update the Social Security Regulations so that the cancers most commonly suffered by firefighters are presumed to be industrial injuries. This should be mirrored in the UK’s Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefits Scheme.”

In a 23 July 2020 response, the government confirmed that it would instruct HSE to monitor the research and to ensure fire and rescue services identify risks to firefighters.

But the government’s Industrial Injury Advisory Council sets a high ‘relative risk’ bar for this recognition, which means thousands of additional work-related cancers could be occurring but wouldn’t under current rules ever be accepted under the scheme.

Hazards warned in 2015 that this system did not recognise for compensation seven of the top 10 entries on the Health and Safety Executive’s (HSE) official UK occupational cancer risk ranking (Hazards 129). Five years on, the situation remains unchanged.

Prevention is key

The UCLan report makes a series of urgent recommendations to minimise firefighters’ exposure to toxic fire effluents, including:

| • | Every fire and rescue service must implement fully risk-assessed decontamination procedures en route to, during and after fire incidents, and ensure staff are trained in implementing procedures. |

| • | Fire and rescue personnel should receive regular and up-to-date training on the harmful health effects of exposure to toxic fire effluents, and how these exposures can be reduced or eliminated. |

| • | Firefighters should wear respiratory protective equipment at all times while firefighting, including after a fire has been extinguished, but is still ‘gassing off’. |

| • | PPE should be clean and thoroughly decontaminated after every incident. |

• |

Firefighters should shower within an hour of returning from incidents. |

| • | Regular health screening and recording attendance at fire incidents over the course of a firefighter’s career. |

Anna Stec, professor in fire chemistry and toxicity at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) and the report’s lead author, said: “These recommendations are vital if we are to improve firefighters’ health and well-being, keep them safe and prevent exposure to toxic chemicals, which can lead to life-changing problems or premature death. They must be implemented swiftly to reduce the health risks firefighters face.

“This report highlights some of the risks and sources of contamination that firefighters are exposed to on a regular basis, and how these can be controlled. We hope that this guidance will be adopted and used by the fire sector across the UK and beyond so the overall exposure of firefighters and their families is reduced.”

Fighting fires

Inaction is not an option, says FBU. “There are some hard truths for fire and rescue services in this report – and far more needs to be done to protect firefighters from cancer and other illnesses,” said FBU’s Matt Wrack. “The Health and Safety Executive must urgently implement the recommendations to bring life-saving measures into place as soon as possible.”

He added: “Every firefighter knows the fear that, someday, they and their family could receive the devastating news – but we’re determined to do all we can to reduce the risk of firefighters developing these terrible diseases as a result of their job.”

Earlier action by the government and HSE could have saved Sid the trauma of a cancer diagnosis and treatment. “Contaminants were not understood for much of my time in the service and therefore weren’t taken seriously. When I joined, we wouldn’t even wear breathing apparatus when attending fires in the open, including car fires,” he said.

“Nowadays there are a lot more precautions and my station definitely overcame that badge of honour culture where we were proud of our dirty kit. If the current recommendations had been in place when I first joined the service, I am in no doubt that they would have made a difference to me and my colleagues.

“If we’d known and we’d had these measures, we’d have used them and fewer of us would have got sick.”

| • | Minimising firefighters' exposure to toxic fire effluents: Interim best practice report, UCLAN, November 2020. www.uclan.ac.uk; www.fbu.org.uk |

| • | IAFF list of presumptive legislation on cancer in firefighters across North American jurisdictions. |

Emergency workers in diesel cancer risk group

Professional drivers are facing a routine and serious health risk from diesel exhaust fume exposures at work, a UK study has found, with drivers working for the emergency services in the high risk group.

In what they described as “the largest real-world in-vehicle personal exposure study to date,” researchers from the MRC Centre for Environment and Health, Environmental Research Group and Imperial College London, found that professional drivers are regularly exposed to hazardous levels of diesel emissions as part of their work.

The DEMiSt study funded by safety professionals’ organisation IOSH found that professional drivers are disproportionately affected by exposure to diesel exhaust fumes, including taxi drivers – the worst hit group – couriers, bus drivers and drivers working for the emergency services.

Dr Ian Mudway of Imperial College London, who led the DEMiSt research team, said: “We believe there are around a million people working in jobs like these in the UK alone, so this is a widespread and under-appreciated issue – indeed, it was very noticeable to us just how surprised drivers taking part in the study were at the levels of their exposure to diesel.”

In total, 11,500 hours of professional drivers’ exposure data were analysed in the baseline monitoring campaign. The results showed that, on average, professional drivers were exposed to 4.1 micrograms of black carbon per cubic metre of air (µg/m3) while driving, which was around four times higher than their exposure at home (1.1 µg/m3). The levels recorded at home would be similar to levels experienced by office workers at their desks, the researchers said.

The study found massive exposure spikes often occurred in congested traffic within Central London, in areas where vehicles congregate, such as in car parks or depots, as well as in tunnels and ‘street canyons’ (between high buildings).

‘Fuming’, a 2018 report from Hazards, linked diesel fume exposure at work to lung and blood cancer and heart, lung and other diseases.

| • | Lim S, Barratt B, Holliday L, Griffiths C, and Mudway I. The driver diesel exposure mitigation study (DEMiSt), IOSH, November 2020. www.iosh.com |

SMOKING GUN

Firefighters risk their lives to save ours. But work-related cancers caused by routine toxic exposures, both at incidents and in training, could be a far bigger risk to their health, warns Hazards editor Rory O’Neill.

| Contents | |

| • | Introduction |

| • | Where there’s fire |

| • | Exposed by design |

| • | Cancer consequence |

| • | Prevention is key |

| • | Fighting fires |

| Other stories | |

| • | Emergency workers in diesel cancer risk group |

| Hazards webpages | |

| • | Hazards news |

| • | Cancer |

| • | Work and health |