Safety in the pits

Hazards issue 116, October-December 2011

It appeared like a grim but thankfully rare reminder of Britain’s dirty and dangerous industrial past. When water broke through from old adjacent workings at Gleision drift mine at Cilybebyll in the Swansea valley on 15 September 2011, there was a fleeting hope that Garry Jenkins, 39, David Powell, 50, Phillip Hill, 45 and Charles Breslin, 62, might survive. But the four miners, part of a team of seven working in the mine, all drowned, and the focus quickly turned to the cause.

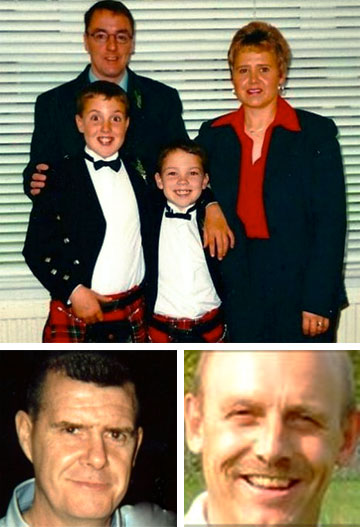

WASTED LIVES Charles Breslin and Phillip Hill (top) and Garry Jenkins and David Powell (bottom) all drowned when a South Wales coal mine flooded in September 2011.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) on 23 September 2011 issued a safety alert warning mine companies of the danger of an inrush of water at underground mines. HSE said its safety alert was “to remind owners and managers of producing mines of the precautions to be taken against inrushes and to request owners confirm that such measures are being taken at the mines that they operate.”

Then on 18 October 2011, pit manager Malcolm Fyfield, 55, was arrested by officers from South Wales Police on suspicion of manslaughter. Something had gone tragically wrong, and there were rumours the deaths occurred as the team worked in an off-limits, unauthorised but coal rich section of the seam.

UK Coal’s deadly record

The four killed in South Wales weren’t to be September’s only mine victims. Gerry Gibson, a 49-year-old father of two, was killed on 27 September 2011 and a colleague was injured when a roof collapsed at Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire.

Concerns about safety standards at UK Coal, the coal giant operating Kellingley and which employs 2,900 people in three massive mines, are not new.

Gerry Gibson – right, with wife Brenda and sons Sean and Andy - was the third miner to be killed at Kellingley in the last four years. Ian Cameron (bottom left) died after equipment fell on him on 18 October 2009 and in September 2008, Don Cook (bottom right) died in a rock fall.

And the company has deadly blemishes on its safety record at other pits. Three workers died in separate incidents at the company’s Daw Mill mine in Warwickshire in the eight months up to January 2007 and a further miner died at UK Coal’s Welbeck colliery in Nottinghamshire in November 2007.

On 30 November 2010, UK Coal had to evacuate 218 workers from Kellingley after methane gas seeped into the area and ignited. Then on 12 October 2011, just two weeks after Gerry Gibson’s death, HSE was called to another fire and evacuation at the pit.

Andrew McIntosh, communications director with UK Coal, commenting after Gerry Gibson was killed, said: “Those who work here know how hard we push health and safety. Everyone understands this is a hazardous place to work, in the mines, which is why it is down to all of us to ensure we work as safely as possible.”

But the mines are not as safe as possible. Mining unions say the fatality rate has soared since they were privatised.

Deaths are not inevitable

Official figures obtained by Hazards reveal over the five years to 2010/11 the fatality rate in the UK coal mining industry has been running at 42.9 deaths per 100,000 workers – over 60 times the all-industries rate of 0.7/100,000 for the same period. HSE indicate its figures should be read with caution because “as the industry gets smaller the impact of a small number of fatalities can cause significant fluctuations year on year in rates.”

DEADLY RECORD Seven workers have died in separate incidents at UK Coal pits in the last four years, three of them at Kellingley Colliery.

But HSE’s decision to only provide the five year average figures – Hazards asked for year-on-year comparisons, but these statistics were not forthcoming – can also mask years where the industry’s performance was particularly bad. Five workers were killed in in UK coal mines in 2006/07, a rate of around 125 per 100,000. That number had been reached half way through the 2011/12 reporting year, suggesting a rate in at least matching and in all tragic probability probably in excess of the 2006 high.

Even accepting there will be fluctuations, the UK coal industry has not had a single fatality-free year in the last six. The six years before that saw one fatality in total. This year’s flurry of deaths will push the average rate in the six years from 2006 to in excess of 47 deaths per 100,000 workers - a 50-year high.

In a statement to Hazards, HSE admitted: “The last time the equivalent rate of fatalities in coal mining was in the range of 40 per 100,000 was in the early sixties when we estimate it was 46.”

INHERENTLY WRONG International mine safety expert Dave Feickert says HSE is wrong to claim mining is inherently dangerous. Some coal mines have no injuries, not just no fatalities, he says. [see full interview]

It is a statistic that shocks mining expert Dave Feickert (right). The former National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) head of research says that when the mines were nationalised in 1946, they inherited a private industry death rate of 80 deaths per 100,000 workers.

The more closely regulated, publicly owned mines quickly became safer. By 1953 the rate was down to 55 per 100,000 workers. The rapid improvements continued, so by the late 1980s, the fatality rate in National Coal Board mines had fallen to 10 per 100,000 – less than a quarter the industry’s current fatality rate. The UK fatality rate hasn’t been anywhere near that good in any of the last six years.

Feickert has been down Kellingley pit on several occasions. “In a developed country like Britain, fatalities should be an aspect of the country's tragic mining past,” he says. “There is no reason why Kellingley cannot have a zero accident rate, especially when there are mines with no injury - not just no fatalities - in a year.”

Ken Capstick (right) , a former vice-president of Yorkshire NUM, is scathing about UK Coal. “This employer has been able to exploit the much reduced influence of the mining unions since privatisation and has ruthlessly imposed drastic working conditions on its workforce,” he says.

Ken Capstick (right) , a former vice-president of Yorkshire NUM, is scathing about UK Coal. “This employer has been able to exploit the much reduced influence of the mining unions since privatisation and has ruthlessly imposed drastic working conditions on its workforce,” he says.

HSE sees it differently. Its mining webpage notes: “The number of mining personnel killed or seriously injured in mining related accidents has gradually declined due to the continual commitment from operators, unions, and HM Inspectorate of Mines staff and as a result the UK continues to be the world leader in mining health and safety.”

Dave Feickert says the falling number of deaths reflects an industry which once employed over 1 million miners but now has fewer than 4,000 workers, over half working for UK Coal. The body count is lower, but the chances of each UK miner dying is now considerably higher than 30 years ago.

The deaths at Gleision and Kellingley should be “a wake-up call for Britain's coal mines and its system of health and safety regulation and practice,” Feickert says, adding the nature of the safety malaise in Britain’s mining industry has “been well known in the industry for some time… less vigilant safety practice, a lighter regulatory touch and less trade union involvement in safety.

“There was a time not so long ago that Britain could claim to have one of the safest coal industries in the world. Sadly, this is no longer the case and it seems, the fewer the mines, the higher the accident rate goes, compared with the 1970s and 1980s.”

He says privatisation was a turning point. “The safety culture changed in British mining after that. For the 10 years preceding privatisation the NUM and the pit deputies’ union, NACODS, fought a long rearguard action to defend the Mines and Quarries Act 1954.

“This long struggle was only partly successful. The role of the pit deputy was weakened, although that of the workmen's inspector was kept. Now the cuts in the HSE have weakened checks by the mines inspectorate.” HSE has just 12 mine inspectors nationwide, covering 118 working sites including 21 licensed underground coal mines.

HSE’s deadly optimism

HSE’s belief in a “continual commitment” by all parties is just plain wrong, Feickert says, with the industry typically paying less regard for safety, the mining unions no longer present in all the mines and with curtailed safety rights where they are present, and HSE doing less with less.

“Sadly, large British mines like Kellingley and Daw Mill in recent years have been less safe than some comparable large mines in China. There are relatively new mines in China which have not had a single fatality… the simple fact is China is getting better while the UK is getting worse.”

China’s official death toll for 2010 was 2,433, but that is in an industry employing over 4 million miners. It amounts to an official death rate for China’s coal mines not too far distant from that in the UK. The China figures may be suspect, but they are at least heading in the right direction, down from almost 7,000 deaths a year in 2002.

When pressed, HSE’s defence of the UK mining industry’s record begins to crack. The safety watchdog told Hazards: “A deterioration in the long-term improvement began to emerge in the last five years and, given the reduced size of the industry, was both pronounced and of concern to HSE.” It added: “We are focused on ensuring through our interventions that improvements in the industry are keeping pace with the changing activity levels in mining.”

HSE says it has a plan. “Mining is an inherently dangerous industry and we are focused on making sure the present intervention strategy for the sector is properly targeted on the main hazards such as ground collapse, fire, explosion, gas and ageing plant,” it told Hazards. “As part of our approach to reversing this decline we have sought the views of the mining TUs [trade unions], major employers, Mines Rescue Service and organisations representing smaller mines on the priorities for improvement so the sector strategy represents the consensus of all parties, not just HSE.

“The Mining Industry Safety Leadership Group was formed to take this strategy forward in conjunction with HSE. We are focused on ensuring through our interventions that improvements in the industry are keeping pace with the changing activity levels in mining.”

In a subsequent clarification, HSE told Hazards: “The key point… is that the current performance is a cause for concern and we are focusing our efforts on the risk creators to improve the effectiveness of their reduction and management of those risks.” The HSE mine sector health and safety strategy, published in March 2011, says the “first stage” of these efforts “will be to invite duty holders to self-assess” their “leadership, competence and safety performance.”

Ken Capstick believes putting so much faith in what HSE says is an “industry led” leadership group and the industry’s self-assessment of its own shortcomings is a mistake. He says the reason UK mines are getting more hazardous is because the leadership of the mining companies are turning the screw. “Miners at Kellingley now work 12-hour shifts underground as a matter of routine, with shift patterns that are unacceptably disruptive to natural life and create both mental and physical fatigue in an already high stress industry.”

He adds: “Under the company’s latest demands pensions, wages, bonuses, shift patterns and redundancy terms will all come in for further attacks with a threat that if these conditions are not accepted they will be forced through.”

This is a prospect he finds chilling. “I predict that if UK Coal is able to force through its latest demands, miners at the colliery will be subjected to even more stressful working conditions with a corresponding adverse effect on morale and further accidents, fatalities and near-misses.”

HSE was already placing more faith in firms, despite their deteriorating fatalities record. The use of roof bolts in coal mines requires an explicit HSE exemption from the mines support regulations, which were introduced to protect miners from deadly roof falls. A request for an exemption used to result in HSE inspections before and three months after the roof bolts were introduced. Not any more. One former HSE mines inspector told Hazards: “Now the manager simply notifies the inspector of his intentions and no inspections are made. It is a form of self-regulation that has never worked.”

There are other questions about HSE’s role. The watchdog visited Kellingley five times in the six months prior to Gerry Gibson’s death. The last of these visits, on 15 August 2011, was to the new 502 coal face on which the death occurred. HSE took no action at the time. Six weeks and one fatality later HSE visited the same coal face and issued two improvement notices, both relating to criminal health and safety breaches on the face.

Commenting on this latest fatality, Ken Capstick says: “If this latest fatality changes the ethos in Britain’s coal industry that has followed privatisation, then Gerry Gibson may have died unnecessarily, but not in vain.”

References

People's Republic of China - Coal Mine Safety Study, Part II, International history and experience with coal mine accidents, page 20, Asian Development Bank, (undated, part II believed published in 2008).

Mines Sector Health and Safety Strategy 2011 to 2013, HSE, March 2011.

Use of rockbolts to support roadways in coal mines, HSE, 2007.

UK Coal can expect low death fines

A judge has indicated he will not impose heavy fines on UK Coal after four miners died following criminal safety breaches at the UK’s biggest mining firm. Justice Alistair MacDuff adjourned sentencing of UK Coal, which admitted offences under health and safety laws in relation to the deaths of Trevor Steeples, Paul Hunt, Anthony Garrigan and Paul Milner.

Mr Steeples, Mr Hunt and Mr Garrigan died in separate incidents at Daw Mill Colliery, near Coventry, in 2006 and 2007. Mr Milner died following an incident at the now-closed Welbeck Colliery in Nottinghamshire in 2007. In an October 2011 hearing, Sheffield Crown Court heard how the firm was “under intense economic pressure” following the recession. UK Coal's solicitor Mark Turner told the court that shares worth £5 five years ago recently traded for 34p.

He said it was in a “very poor way financially” and was implementing a survival plan. The Doncaster-based company reported losses of £124.6m in 2010, following losses of £129.1m in 2009 and £15.6m in 2008.

The judge told Sheffield Crown Court he had a very difficult exercise to perform to provide justice for the men's families yet not threaten a company which “provided energy to the nation, employment within the nation and a valuable service all round.” The judge said it would be in “nobody's interest” to impose devastating financial penalties.

The fines would be announced in late November or early December 2011, he said, warning family members watching from the public gallery that the fines might be lower than some might expect. The judge said he would first establish a total figure UK Coal should be liable for and then deduct the costs before determining the level of fines.

The legal costs are estimated to be £1.2m, not including the bill for the adjourned 20 October court hearing, UK Coal’s Mark Turner said.

In contrast to serial offender UK Coal, it may be a person rather than a faceless company that appears in the dock on charges relating to the four September 2011 deaths at the Gleision Colliery in South Wales. Pit manager Malcolm Fyfield, 55, was arrested on suspicion of manslaughter in October.

Dave Feickert interview

International mine safety expert Dave Feickert spoke to Hazards on 28 September 2011.

Personal note - I have been underground at Kellingley colliery on several occasions. This magnificent group of men deserve so much more than this - like miners elsewhere they have the fundamental right to return to their family after every shift. In a developed country like Britain, fatalities should be an aspect of the country's tragic mining past. There is no reason why Kellingley cannot have a zero accident rate, especially when there are mines with no injury - not just no fatalities - in a year.

The fatal accidents at two UK coal mines, in South Wales and Yorkshire in less than two weeks are a wake-up call for Britain's coal mines and its system of health and safety regulation and practice. Investigations are taking place, but the main outlines of the problems have been well known in the industry for some time. These are: less vigilant safety practice, a lighter regulatory touch and less trade union involvement in safety.

Why has nothing been done? There was a time not so long ago that Britain could claim to have one of the safest coal industries in the world. Sadly, this is no longer the case and it seems, the fewer the mines, the higher the accident rate goes, compared with the 1970s and 1980s. the privatisation of the remaining mines was a factor. The safety culture changed in British mining after that.

For the 10 years preceding privatisation the NUM and the pit deputies union, NACODS fought a long rearguard action to defend the Mines and Quarries Act 1954. This long struggle was only partly successful. The role of the pit deputy was weakened, although that of the workmen's inspector was kept. Now the cuts in the HSE have weakened checks by the mines inspectorate.

Sadly, large British mines like Kellingley and Daw Mill in recent years have been less safe than some comparable large mines in China. There are relatively new mines in China which have not had a single fatality. Of course, there are other older mines with low levels of mechanisation and poorer safety standards where scores have been killed in gas explosions and flooding.

But the simple fact is China is getting better while the UK is getting worse. It is true that in China, the official fatal accident figure in coal mines is likely to be over 2,000 in 2011. This has come down from nearly 6,995 in 2002. But the industry employs over four million miners. Production in 2011 is scheduled to reach over 3.5 billion tonnes. The most the UK produced in a year reached less than 10 per cent of that. It was at a time the UK had a one fuel economy and over one million miners.

Fatal accident rates then were much higher than China today - since records were first kept in the UK in 1850, over 100,000 miners have been killed at work, with many tens of thousands dying from industrial disease. But this enormous suffering produced a long and successful campaign for health and safety improvements. Workmen's inspectors were created in 1872 and became embodied in legislation later - as special safety representatives with more powers than the safety reps under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. They make inspections on a regular basis, send their reports to the manager and the mines inspector and the inspector must respond to points made.

In China there are still over 10,000 small private mines with primitive technology and poor safety practices. In the last few years the government has closed around 20,000 others on safety grounds or merged them into large state-owned mines nearby. As a result China has had to import more coal from Australia especially to fill its requirements for coking coal.

The tragic loss of four miners in South Wales, less than two weeks before the latest Kellingley fatality, points up the special dangers of working in small private mines. Under-capitalised, they have always in every country been less safe than larger, more modern mines with greater investment. Despite this, no British miners have been killed by a colliery flooding since the Lofthouse disaster in Yorkshire. The present regulations on inrushes of water were drafted after the public inquiry into the deaths of the 8 Lofthouse men. They have been updated since.

Managers must have a scheme to deal with water hazards and limits are set for working close to areas where old working are known or thought to exist. Modern techniques can be used to determine nearby flooding of old workings. At Gleision colliery in South Wales we don't yet know the details but, it is likely that the men were working too close to old workings. Why was that, will be the key question of the investigation.

As far as the deaths at Daw Mill, Kellingley and Welbeck collieries in recent years are concerned - these have all been separate incidents. In the case of Kellingley and Daw Mill, this is what is shocking. Most of these deaths have resulted from falls of ground - either roof or tunnel walls. The HSE should examine all of these together now to determine any common factors. In the last few decades rock or roof bolts have come to be frequently used. There needs to be a detailed investigation into how they are used, in what type of strata and with what length of bolt among other things. IT ALSO SEEMS THAT CONVENTIONAL SUPPORT SYSTEMS MAY NOT HAVE BEEN USED TO FULL EFFECT TO KEEP THE MEN SAFE.

The death of a pit deputy by asphyxiation from methane at Daw Mill in 2006 is particularly shocking. How could a deputy, highly trained in dealing with methane gas, come to be in such a situation? The third fatality at Daw Mill involved a vehicle running over a miner underground. The hazards of using large machines underground was appreciated when they were first introduced and a risk assessment of their use should be made for every mine and continuously updated to deal with the changing road layouts.

Two other incidents speak to a need for an overall investigation into the state of safety and health practice and regulation of British mines. These were the methane gas ignition at Kellingley colliery at the coal face and the withdrawal of all the men to the surface. They remained out of the mine for a lengthy period, while the problem was resolved. The second is the cage at Maltby colliery which was stuck in the shaft, with 18 men in it, in sub-zero conditions.

However, what needs to be said as well, is that the Mines Rescue teams have acted with bravery and competence when called out, especially recently at Gleision colliery and at Kellingley. During the gas ignition incident at Kellingley the emergency management team which included mine management, HM inspectors, mines rescue and trade union representatives worked very well. This proved that continuous training and practice can help in critical situations. But the simple fact is, the miners should not be put into this situation in the 21st century in a developed country.

This is the same message I tell the Chinese government and industry colleagues here in China and most of them are doing their best to make things better.

Dave Feickert worked for the NUM from 1983 -1993 and works now as a coal mine safety adviser in China and New Zealand, where he now lives.

Ken Capstick interview

Ken Capstick, a former coalminer, former vice-president of the Yorkshire National Union of Miners, and former editor of the NUM journal The Miner, spoke to Hazards on 1 October 2011.

Ken Capstick, a former coalminer, former vice-president of the Yorkshire National Union of Miners, and former editor of the NUM journal The Miner, spoke to Hazards on 1 October 2011.

The latest fatality at Kellingley Colliery, in which faceworker, Gerry Gibson, was killed, highlights ongoing problems at the North Yorkshire pit for which owner, UK Coal, must be brought to task. There have been three fatalities at the colliery in as many years regardless of a much reduced workforce from that of its heyday in the 1960s and 70s.

At the mining firm’s other collieries, Daw Mill, in Warwickshire, Thoresby and Welbeck, in Nottinghamshire, there have been five fatalities in the last five years, a consistently dismal record. A total of eight fatalities in that one short-period, in what is now a very small industry, are totally unacceptable. One of those miners, Paul Milner, 44, died at Welbeck, under 90 tonnes of fallen rock.

UK Coal said it had “commissioned an independent inquiry into safety practices and procedures within UK Coal and especially at Daw Mill.” But it has admitted criminal breaches of safety standards already.

Do I trust UK Coal’s assurances that Kellingley is a safe pit? I am afraid I can’t.

This employer has been able to exploit the much reduced influence of the mining unions since privatisation and has ruthlessly imposed drastic working conditions on its workforce. Miners at Kellingley now work 12-hour-shifts underground as a matter of routine with shift-patterns that are unacceptably disruptive to natural-life and create both mental and physical fatigue in an already high-stress industry.

Regardless of the sign outside the colliery portraying the vision of a safe and happy family pit and boasting on its website that it “is very aware of the need to ensure the wellbeing of employees in the business environment and their vision is to work with their employees to secure health,” the company is currently horns-locked with its workforce as it attempts to impose even more stringent terms and conditions with a threatening - or else - caveat.

Under the company’s latest demands pensions, wages, bonuses, shift patterns and redundancy terms will all come in for further attacks with a threat that if these conditions are not accepted they will be forced through. This year’s agreed 4.5 per cent wage increase has been withdrawn and replaced with a 1 per cent decrease, so much for happy families.

I predict that if UK Coal is able to force through its latest demands miners at the colliery will be subjected to even more stressful working conditions with a corresponding adverse effect on morale and further accidents, fatalities and near-misses.

Just before Christmas the mine had to cease production for two weeks after methane explosions had occurred on the coalface. Explosions in coalmines can, and have, killed hundreds of miners in the blink of an eyelid and the workforce was extremely lucky that the incident did not lead to multiple deaths. Britain’s worst mining disaster was as a result of an explosion at Gresford Colliery, in North Wales, in 1934 when 266 miners died.

There must be a full inquiry into this latest fatality and it should be expanded to look at the wider causes than just the site of the disaster and the details of this particular fatality, it must include the intolerable attempts to impose even hasher demands on the workforce, stress levels at the colliery must be evaluated independently and older and wiser miners, with hands-on experience, working at Kellingley, must be involved in finding a solution to what is developing into a disturbing trend.

If this latest fatality changes the ethos in Britain’s coal industry, that has followed privatisation, then Gerry Gibson may have died unnecessarily, but not in vain.

Safety in the pits

Why is the death rate in Britain’s coal mines at a 50-year high? Because the industry is out of control.

Contents

• Introduction

• UK Coal’s deadly record

• Deaths are not inevitable

• HSE’s deadly optimism

• References

Hazards spoke to mine safety experts Dave Feickert and Ken Capstick about their concerns for mine safety in the UK.

Hazards spoke to mine safety experts Dave Feickert and Ken Capstick about their concerns for mine safety in the UK.

Read the full interviews here.

Related story

UK Coal can expect low death fines A judge has indicated he will not impose heavy fines on UK Coal after four miners died. In October 2011, Justice Alistair MacDuff adjourned sentencing of UK Coal, which admitted criminal safety offences in relation to the deaths of Trevor Steeples, Paul Hunt, Anthony Garrigan and Paul Milner. more

Hazards webpages

Vote to die • Deadly business