Once in a lifetime

HSE inspection and enforcement drops off the chart. Hazards issue 110, April-June 2010

A worker is blinded. A High Court judge rules the firm is 100 per cent liable. It would seem to be a copper bottomed case for rigorous Health and Safety Executive (HSE) enforcement action. But there will be no prosecution. And, as new figures obtained by Hazards show, the watchdog is being seen less in Britain’s workplaces and taking fewer prosecutions when it does show up.

It is workers like Mark Downs who are losing out. He was left blind and with serious brain injuries when he was hit on the head by a five and a half tonne metal sheet. The 39-year-old (below right) was crossing the factory floor at Hadee Engineering Ltd in Sheffield when the sheet, which was being manoeuvred in a tandem lift, swung out of position and knocked him against a steel skip.

BLIND ALLEY The Health and Safety Executive says it won’t prosecute the firm “100 per cent liable” for blinding Mark Downs at work. Figures obtained by Hazards show the safety watchdog is rarely seen in Britain’s workplaces any more, and is far less likely to act when it does turn up.

The incident left him blind and paralysed down his left side. He has also lost his sense of smell and taste. He will never work again and will, in all probability, require lifelong assistance. His family even had to fight for the compensation that will pay for his long-term care.

Hadee Engineering refused to accept full liability for the welder’s injuries – he required a 16 hour operation to treat a deep skull fracture, brain contusions and a right sided haemorrhage, and multiple fractures to both eye sockets – forcing Mark’s family to turn to the courts.

At Sheffield High Court on 3 March 2010, Mr Justice MacDuff QC ruled that the employer was fully liable. The judge criticised Hadee Engineering Ltd for seriously breaching a number of health and safety regulations, including failing to properly supervise the tandem lift, not carrying out a risk assessment, not holding a written method statement, operating without a banksman or supervisor and failing to properly train one of the crane drivers. He also ruled that Mr Downs was entitled to 100 per cent of the final settlement for his injuries. The payout is likely to run to millions.

Lawyer Rachael Aram, a brain injury specialist at Irwin Mitchell Solicitors, represents the family. She said: “This horrific accident should never have happened, and had Mr Downs’ employers followed basic health and safety regulations it would have been avoided.”

REGULA-TORY SCOUNDRELS Construction union UCATT protested outside Tory party HQ on 27 April, outraged by a Conservative push for health and safety deregulation (Hazards 109). HSE inspectors’ union Prospect described David Cameron’s plans as “sheer lunacy”. And the Hazards Campaign said Tory plans to “privatise” safety enforcement were “a scoundrels’ charter.”

Despite the High Court judge finding the company was responsible for serious and numerous breaches of safety legislation, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) had earlier decided it would not pursue a prosecution – and is standing by its decision.

HSE regional director David Snowball told Hazards: “It would not be appropriate for HSE to comment on what the Judge said in court but a senior operational manager has now completed a review of the HSE investigation. This has confirmed that the original HSE decision not to prosecute was correct because the available evidence, particularly of custom and practice for access into the area concerned, fell short of the standard of proof required for a realistic prospect of a successful conviction in a criminal case (ie. beyond reasonable doubt).”

It’s a claim questioned by Mark’s lawyer, Rachael Aram. While accepting the higher burden of proof required in criminal prosecutions, as opposed to the “balance of probabilities” in civil compensation cases, she says “there clearly were huge statutory breaches.” The particulars of claim submitted to the court by Mark Downs’ legal team included 22 explicit allegations of negligence. Of these, 15 were in relation to breaches of safety law - the management of health and safety at work, work equipment, lifting and welfare regulations - with the remainder relating to common law offences.

The High Court judge left little room for doubt about Hadee Engineering’s culpability, noting the defendant had at best “a cavalier attitude” to health and safety.

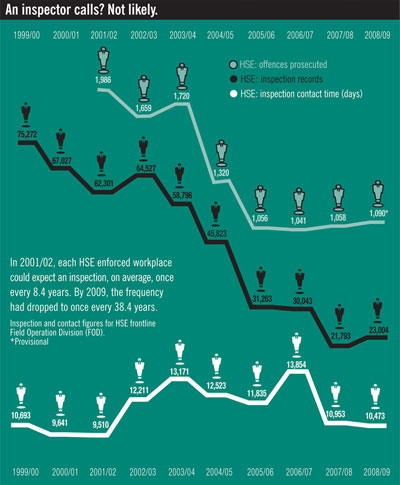

Figures obtained by Hazards suggest HSE’s reluctance to prosecute might have had as much to do with resources as the law. In 2001/02, HSE enforced safety at an estimated 525,841 workplaces. Latest figures show the much diminished inspectorate is now responsible for 884,000 workplaces.

Over the period, the number of HSE inspections has plummeted. A decade ago, the frequency with which HSE was likely to turn up at your workplace was once every 8.4 years.

Last year, with HSE faced with more workplaces and fewer frontline inspectors in its field operations division (FOD), that frequency had dropped to once every 38.4 years.

HSE’s defence, used before parliamentary panels, at conferences and in press statements, was that it was doing fewer inspections, but doing these more thoroughly. It backed this up with statistics showing it was achieving an unprecedented level of “inspection contact time.” Figures presented to Hazards by HSE in October 2009 appeared to bear this out – over the last three years, the amount of “inspection contact time in days” had gone from a low of around 9,500 days in 2001/02, to in excess of 15,500 for each of the last three years.

Another death, another casualty?

Will the Health and Safety Executive prosecute a firm where a laundry worker was crushed and later died? The watchdog doesn’t seem to know.

City Linen Services in Birmingham neglected to guard a machine or post warning signs about serious safety risks, but it didn’t stop it putting an unsupervised notice on the job. Hafiz Abdul Shakoor fell into a coma and died of a heart attack 12 days after being trapped between metal bars in the laundry loading area. He had climbed up the rear of the equipment in an attempt to fit a new laundry bag. But this triggered a motion-sensitive mechanism which brought a metal bar down, crushing him.

The 36-year-old began to suffocate and was stuck inside the machine for 20 minutes until firefighters could free him. An inquest jury, which returned an accidental death verdict in March 2010, heard Mr Shakoor had worked for the company for two months but had only been operating the loading machine for two days before the incident on 7 April 2009.

Zahid Chaudhry, one of the company’s four directors, told the inquest Mr Shakoor arrived at work for his 6am shift but “got confused” as there were no empty bags in which to load the laundry. The tragedy happened as he tried to fix a bag left on the floor into position by climbing up the rear of the equipment. City Linen Services co-director Mark Allen told the jury there should have been signs in place stating the machinery should not be climbed on and these had since been installed, as well as a mesh preventing employees from accessing the machine frame.

HSE investigating inspector Pamela Folsom indicated to a reporter from the Birmingham Mail that City Linen Services would not be prosecuted as employees had not been expected to climb on the bagging area machinery.

But when Hazards quizzed HSE HQ on the failure to prosecute, the watchdog backtracked, saying “the investigation is ongoing and no decision on any enforcement action has been taken yet.” It did not respond to requests for an update on the investigation.

Only HSE got its sums wrong. Revised figures provided by HSE show frontline inspector contact time peaked in 2006/07, and has fallen dramatically each year since. Last year’s total of 10,474 days is the lowest since 2001/02 – but since then the number of workplaces enforced by HSE has increased by 68 per cent.

The impact on deterrence should not be under-estimated. If the safety police aren’t patrolling workplaces, then the safety criminals have a lot less to fear. There are certainly far fewer making an appearance in the dock. The number of offences prosecuted by HSE has crashed, down from 1,986 in 2001/02, to a provisional figure of 1,090 for 2008/09.

HSE points to its improving conviction rate, up from 70 per cent plus of offences prosecuted in 2005/06 and 2006/07 to around the 95 per cent mark for each of the last two years. It still means the number of offences prosecuted and the number of convictions obtained has all but halved. And that could be because HSE is dropping the more difficult cases.

David Snowball’s comments suggest HSE is now taking only the cast iron certs, leaving hundreds of cases that should be decided by a judge and jury never getting near a court. Cases like that of Mark Downs. According to Mark’s lawyer, Rachael Aram: “There’s no such thing as a case you can’t lose. I’m astounded at a conviction rate of 90 per cent plus. Cases are being dropped that should go to court.”

It is not just minor offences and injuries that are escaping official scrutiny and action. Hazards revealed in November 2009 that fewer than 1 in every 15 major injuries at work even result in a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) investigation (Hazards 108). And the failure to prosecute in the Mark Downs case is not an exception. There was absolutely no HSE enforcement action in almost 98 per cent of major injury cases.

Prosecutions are not just about collaring the guilty, they are about been seen to hold firms to account. If HSE is only taking cases where it is certain “beyond reasonable doubt” that a conviction will be secured, then firms that in all likelihood are guilty of sometimes heinous safety crimes will be escaping the courts purely on the say so of HSE.

HSE, inevitably, will take the decision not to prosecute with half an eye to its pared-back resources – court cases can sap time and money - and cut its enforcement cloth accordingly. Justice is one casualty. And so are workers like Mark Downs, where the lack of enforcement action makes them a victim of criminal neglect all over again.

Once in a lifetime

Contents

• Introduction

• Blind alley

• Regula-Tory scoundrels

• Another death, another casualty?

Hazards webpages

Deadly business