It’s different now. In Covid times, employers are unusually knowledgeable about the big risk at work and receptive to Health and Safety Executive (HSE) advice, the regulator told MPs on 17 March 2021.

“We have found that the level of compliance on the whole in businesses with the Covid social distancing and other precautions is significantly better than many of the other areas where we would have otherwise proactively taken action,” HSE chief executive Sarah Albon told the Commons work and pensions committee.

And that was why enforcement activity wasn’t a useful metric. “The number of prohibition notices are very low, but we have also done a couple of prohibition notices as well,” the HSE chief said.

How HSE made a ‘serious’ mistake

Hazards has pieced together information from disparate Health and Safety Executive (HSE) documents, and has discovered the regulator abandoned its own hazard classification system and instead gave Covid-19 a workplace transmission free pass.

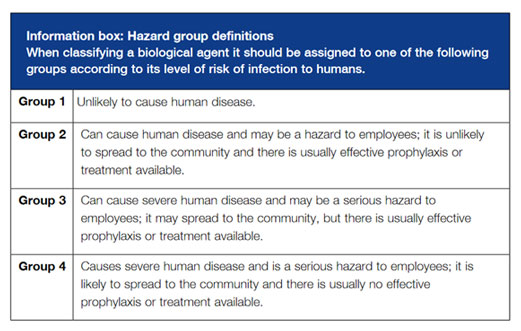

The Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP), the expert committee advising HSE and government, assigned Covid-19 to Hazard Group 3, a designation that under HSE’s Enforcement Management Model should have come automatically with an HSE ‘serious heath effects’ consequence descriptor.

But the ACDP system assumes workplace pathogen risks are limited to hospitals or labs. Covid-19 didn’t fit the model, with the pandemic seeing outbreaks determined by how as well as where people worked. HSE decided to abandon the system and instead downgrade Covid-19 to a less demanding ‘significant health effects’ descriptor.

The significant classification meant HSE’s Enforcement Management Model did not take sufficient account of the rapid spread of Covid-19 through a wide-range of essential jobs, or the impact of millions of infections nationwide on workplace infection rates and fatalities. As Covid-19 outbreaks raced through thousands of workplaces, HSE put its enforcement role on hold.

Read the executive summary

Albon’s brief on her agency’s enforcement record was a little off. Hazards reviewed the records of each of the 910 ‘stop work’ prohibition notices issued by HSE from 25 March 2020, when the Coronavirus Act took effect, until 21 March 2021. In the first full year of the pandemic there had been three prohibition notices issued for Covid-19 related criminal safety breaches, affecting two workplaces, all issued in September 2020.

Construction firm NBA developments Ltd received an immediate prohibition notice because “you have not implemented necessary measures to prevent the spread of Covid-19.”

Spirit Energy Production UK Limited and Jack-Up Barge Operations BV both received immediate prohibition notices for breaches on an offshore oil platform, related to the same criminal breaches. Spirit Energy’s prohibition notice said “the action is necessary as current arrangements on board the platform are insufficient and there is a risk of a serious personal injury from exposure to the virus.”

Other more informative metrics – including regular updates on the number of Covid workplace outbreaks, the affected sectors and related Covid cases – were not made public by HSE. The existence of weekly reports on outbreak numbers, which HSE circulated internally, was only revealed as a result of a 30 October 2020 response to a Hazards freedom of information request.

NO INTELLIGENCE HSE kept to itself its weekly reports on the sectors and geographical areas hit by Covid-19 outbreaks. Shortly after Hazards uncovered their existence, HSE stopped producing the regular updates.

The weekly reports revealed the shocking extent of workplace outbreaks by geographical area and across a wide-range of sectors outside of health and social care. The report for the period to 11 January 2021 revealed the highest number of outbreaks in the preceding days, 223, were in workplaces in ‘non-HRS’ – not in high risk sectors – followed by food manufacture with 139. This compared to just 19 in health and social care.

HSE had in its possession a critical metric which could have informed Covid policies and prevention priorities deployed by industries, unions and other concerned agencies. But HSE kept it to itself.

The 11 January 2021 report proved to be the last. After further freedom of information requests, HSE on 14 January informed Hazards “it has been agreed that there is no longer an operational requirement to produce the report in this format,” adding HSE would “not therefore be producing this report on any regular basis from now on.”

If HSE was still looking at who was getting sick and where, it wasn’t letting on.

Serious concerns

The HSE enforcement response to Covid-19 was a departure from previous practice. Stephen Timms, chair of the work and pensions committee, asked HSE’s Sarah Albon if the dearth of enforcement action reflected a deliberate shift to “informal processes”, stating: “In the year before the pandemic you received altogether about 32,000 concerns and in response you issued just over 7,000 notices. On Covid, up until 4 February, you have received 18,000 concerns and in response you issued 33 notices.”

Albon responded: “Essentially, yes.”

In a 26 March 2021 update, HSE told Hazards: “HSE has resolved 21,115 Covid-related concerns from 10 March 2020 to 25 March 2021. The total number of concerns received exceeds this figure, however some are not for HSE so our role would be merely signposting the appropriate agency.”

SIGNIFICANT MISTAKE HSE inspectors’ union Prospect says the virtual absence of enforcement action against employers in criminal breach of safety laws related to Covid-19 criminal safety breaches work stemmed from the ‘significant’ rather than ‘serious’ consequence descriptor. While over 20 per cent of pre-pandemic concerns resulted in an enforcement notice, that figure for Covid-19 dropped to less than 0.2 per cent. [See: Fetter conceit]

The statement added “as of 25 March 2021, 6,309 concerns have been investigated by operational staff and 1,202 have required a visit to site… 40 concerns have resulted in notices being served (none of these were covid-related prohibition notices); 1,791 concerns resulted in verbal advice being given, and, in 379 concerns, written correspondence was required.”

The statement confirmed these HSE records showed there had been no ‘informations laid’, that would see employers face criminal prosecution and the possibility of a fine.

In the same period, over 68,000 members of the public were fined for breaking lockdown rules.

Albon told MPs this wasn’t a useful comparison. She said HSE had “suffered” from the public’s “completely understandable lack of comprehension that the enforcement we are doing is not the same as the enforcement around groups of people not to gather together or requiring people to wear facemasks in shops.” HSE can’t issue “on-the-spot” fines, she said.

This is true. But HSE’s confidence that enforcement is unnecessary in almost all cases thanks to a new spirit of cooperation from employers, isn’t universally shared.

Unions report many employers have not undertaken or shared risk assessments, or followed Covid-secure practices. TUC deputy general secretary Paul Nowak told the committee the “lived experience of our members and reps is not reflected, we do not think, in the enforcement action from the HSE.”

MINUTE DETAIL HSE has gone into silent mode throughout the pandemic. When Hazards forced it to make minutes of its closed board meetings public, it redacted most of the policy content. Sections on its reworked ‘key priorities’, ‘revised business plan’ and measures to ‘provide an effective regulatory framework’ were blanked out in their entirety.

[See: Enforcement malaise].

HSE – which has been criticised for years for a sharp drop in enforcement activity (Hazards 152) – has operated a virtual enforcement amnesty for Covid-19. According to the latest available figures, concerns reported to HSE regarding Covid-19 were more than 100 times less likely to result in enforcement action than other workplace safety concerns.

One reason is that HSE inspectors weren’t actually doing the inspecting. Prospect’s Mike Clancy told MPs the vast majority of proactive site visits conducted by the HSE in response to Covid have been by external contractors “such as debt collection agencies” – 52,000 compared to 12,000 carried out by trained HSE inspectors.

Two private debt-collection companies – Engage Services (part of Marston Holdings) and CDER Group – were awarded contracts by HSE worth a combined £7m to carry out spot checks on behalf of the regulator. But these tick box Spot Check Support Officers can’t initiate enforcement action, have no right of entry and rarely get beyond reception.

HSE’s decision to assign Covid-19 a second-tier ‘significant’ rather than ‘serious’ risk classification under its Enforcement Management Model (EMM) has been highly contentious. The regulator’s own inspectors have criticised the decision, claiming it informed the soft touch response to Covid-19 ‘concerns’ including criminal breaches of safety law. HSE’s leadership denies this, but there is growing evidence of widespread lawbreaking at work and that this has seen the infection race through workplaces, and victimisation of some of those daring or able to speak out.

ENFORCEMENT FAIL A March 2021 report the Institute of Employment Rights has concluded workplace risks were not mitigated because Covid-19 rules were not adequately enforced. “When the pandemic was declared on 11 March 2020, the government had to decide how it would balance the protection of public health with the protection of the economy,” said report editor Professor Phil James. “A year later, our analysis suggests it got that balance wrong.” [See: Something has gone badly wrong]

The TUC’s latest biennial survey of workplace safety representatives, published on 29 March 2021, found widespread Covid-Secure failures. The survey of more than 2,100 workplace safety representatives reveals employer failures on risk assessments, social distancing and PPE during the pandemic.

More than threequarters of safety representatives (83 per cent) said employees had tested positive for Covid-19 in their workplace, while more than half (57 per cent) said their workplaces had seen a “significant” number of cases. [See: TUC survey reveals widespread Covid-Secure failures].

An October 2020 report from the legal charity Protect found Covid-19 concerns raised by employees were frequently ignored by bosses, with a significant proportion victimising the workers raising safety issues. The best warning system: Whistleblowing during Covid-19 reported 41 per cent of employees raising Covid-19 concerns were ignored by their employers and 20 per cent of whistleblowers were dismissed.

Failed Safe?, a November 2020 report from the Resolution Foundation, found more than one-in-three (35 per cent) workers had an active concern about the transmission of Covid-19 in their workplace – with low-paid workers most likely to be worried, but least likely to raise concerns or see their complaints resolved. The study drew on an online YouGov survey of 6,061 adults across the UK. It found that nearly half (47 per cent) of workers that spend time in the workplace rated the risk of Covid-19 transmission at work as fairly or very high.

HSE’s rationale for informality – when it comes to Covid, employers are uncharacteristically responsible and responsive – also sits uneasily alongside its own data.

On the record?

Under the official RIDDOR reporting regulations, HSE’s website records “over the period 10 April 2020 – 13 March 2021, 31,380 occupational disease notifications of Covid-19 in workers have been reported to enforcing authorities (HSE and local authorities), including 367 death notifications.”

These are low-ball figures. HSE acknowledges RIDDOR, relying on employer reporting of cases, records only a fraction of the true incident. Professor Raymond Agius of University of Manchester’s Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health, who was referenced at the select committee, attempted to quantify the shortfall. He warned in September 2020: “Available evidence suggests that it might have failed in capturing many thousands of work related Covid-19 disease cases and hundreds of deaths.”

Still, the numbers held by HSE are big and the TUC believes not mirrored by a proportionate enforcement response. TUC’s Paul Nowak told the select committee: “I do not think the only metric for the Health and Safety Executive is the number of improvement or enforcement notices or employers being prosecuted, but I think that the balance is wrong and the reality is that employers need to know that if they breach that safe working guidance there is a realistic chance of them being served an enforcement notice by the HSE.

“We are still seeing significant numbers of workplace outbreaks and a report just yesterday in terms of DHL’s facility in Trafford Park.”

On 16 March 2021, the union CWU accused DHL Parcel Ltd of an ‘incoherent’ approach to Covid safety at the Manchester depot, after a third of the workforce was infected. Numbers spiked after a manager who had flu-like symptoms returned to work without taking the mandatory self-isolation period off, or getting a coronavirus test.

Concerned workers raised the matter at a works meeting but were told that the shift manager was “confident” he didn’t have Covid-19. This was despite the manager having come into close contact with another shift manager who had tested positive – and who subsequently died from the virus.

Also in March, a third outbreak hit the 2 Sisters Food Group’s chicken factory in Coupar Angus, this time affecting more than two dozen of its workforce of around 1,000 people. The first outbreak at the factory came in August 2020, with 200 testing positive and all staff sent home to self-isolate for two weeks while the premises were shut down. More positive cases were identified after Christmas, with the number rising significantly through January.

2 Sisters has also had outbreaks at other UK chicken plants. It had to close its Anglesey plant in June 2020 after over 200 workers were infected, nearly 40 per cent of the workforce. This is not a company with a clean record. It has been prosecuted by HSE for criminal safety offences five times since 2010, running up fines in excess of £1.9 million.

Many other food processors, including Bakkavor and Kepak, have had multiple outbreaks, some also seeing hundreds of workers infected.

Outbreaking bad

In figures obtained by Hazards, Public Health England said up to late-January 2021 it had recorded 4,523 workplace outbreaks in England, across a range of sectors. The PHE response to a freedom of information request revealed out of this total, 559 workplace outbreaks were in retail, 687 in offices, 354 in food manufacturing and packaging and 728 in other manufacturing. Several outbreaks, like two at 2 Sisters, saw hundreds of workers infected.

HSE was rarely anywhere to be seen. HSE CEO Sarah Albon told MPs the regulator had been involved in “almost 600 of the outbreaks,” or fewer than 1-in-8.

Nor was the enforcer tracking down the workplace infection hotspots itself. HSE had taken a back seat routinely to public health agencies. Albon told MPs that “reporting of clusters and outbreaks has been at an unprecedented level and has enabled us to get involved… via PHE rather than us bring them into it.” She said even so HSE had the information it needed on areas of concern, adding “frankly we are finding out about outbreaks anyway through the public health system.”

It has been regular refrain from Albon. In a 25 February 2021 letter to Janet Newsham of the Hazards Campaign, the HSE boss stated: “Covid-19 is, first and foremost, a public health issue.”

Covid-19 is a public health issue, with a considerable workplace health contribution, both to infections and transmission. Many concerns, like toxic chemicals or falls from height, are not exclusively workplace health issues. But HSE would baulk at any suggestion it was not its mandate to take the lead on investigations and enforcement when these hazards arose in the workplace. And for Covid-19, lockdowns and ‘essential’ work have meant over the last year the workplace has been one of the few places outside the home there was a substantial risk of exposure (Hazards 151).

There is clear evidence of a substantial workplace effect. An Office for National Statistics (ONS) analysis of Covid-19 deaths by occupation in England and Wales over the period 9 March to 28 December 2020 found shocking excesses in a wide-range of jobs. The figures published in January 2021 – a month that for the first time in the pandemic saw over 1,000 workplace infection cases reported every week to HSE – revealed the excess deaths are most frequently in workers doing often low paid, ‘essential’ jobs.

In males, bakers and flour confectioners had a Covid-19 fatality rate 22.7 times higher than expected. Other high risk jobs included butchers (6.6x) and food and drink workers and care workers and home carers (all 3.5x higher). Men working in manufacturing, health care, cleaning and construction all had rates at least double the expected rate.

Among women, sewing machinists topped the Covid working age fatalities list, with a rate 3.9 times expected, followed by care workers and home carers (2.8x), chefs (2.5x) and retail workers, houseparents and residential wardens and social workers (all 2x).

Asked at the March 2021 work and pensions committee hearing whether its strategy “reflected a complacent attitude to the virus as a whole last year,” Albon responded: “I have to refute that.

“We are the opposite of complacent. We are.”

DEBT RELIEF HSE’s Covid-19 response has been severely hampered by a lack of resources, as a result of cuts of 54 per cent in real terms since 2010. Instead, much of the work has been outsourced to two debt-collection companies with no work safety track record – Engage Services (part of Marston Holdings) and CDER Group – who undertook over 80 per cent of all ‘HSE’ Covid visits. [See: Follow the money]

Critics say HSE’s decision under its Enforcement Management Model (EMM) not to classify Covid-19 as a ‘serious’ hazard has thrown doubt on this assurance, with evidence the controversy is causing consternation within the regulator. HSE first denied then conceding it is reviewing the designation to take account of the latest scientific evidence, with the findings of its literature review due late April 2021.

For now, though, the regulator continues to defend the ‘significant’ classification. It argues it hasn’t been complacent, it has been misunderstood. HSE chief executive Sarah Albon told MPs that in assigning a significant “consequence descriptor” for Covid-19, “we are not using the word ‘significant’ or ‘serious’ in their normal English meaning.”

HSE’s website picks up the theme noting, “this classification may have incorrectly given the impression that HSE is treating the pandemic as not serious. Nothing could be further from the truth as we have been dedicated, alongside other government departments during the pandemic, to helping employers keep workplaces Covid-secure.”

Commenting on the number of Covid-19 deaths in people of working age, Albon told the committee: “Some 11,000 people dying is a desperate tragedy for those people, their families and their friends” and “nobody is trying to play down the seriousness of this, but it is much more likely to [have] a serious or fatal consequence for those people outside of working of working age.” She said age and comorbidities were the two biggest factors responsible, adding: “It is important to recognise that the 11,000 people are not 11,000 people who were all in work.”

We do know, however, people under the age of 65 in the UK were dying in greatly increased and peculiarly high numbers last year. A 19 March 2021 report from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) noted that in Europe only Bulgaria had a higher excess of deaths in this age group.

There is clear evidence work is a significant contributor. A 25 January 2021 report from ONS, which was adjusted for age, identified a stark excess of deaths from Covid-19 in those doing ‘essential’ jobs – whether in manufacturing, transport, retail, care or social services.

REAL LOSS Unite has paid to tribute to ‘well-loved and respected’ Brighton bus driver Christopher Turnham following his death from Covid-19. The 58-year-old, a longstanding Unite workplace representative, died on 20 January 2021 shortly after falling ill with Covid-19. A December 2020 study in the journal Occupational and Environmental Medicine found the risk of getting severe or fatal Covid-19 is twice as high for workers in England with jobs in transport and the ‘social and education’ sectors, and seven times higher in health care.

None of these jobs are characterised by an especially old or unhealthy workforce. Even within these high Covid mortality occupational groups, many of those with pre-existing health conditions or vulnerabilities have been required to stay away from work and ‘shield’. What the jobs with a high mortality rate do have in common is little prospect of furlough and little or no chance of working from home.

Public Health England’s breakdown of outbreaks in ‘workplace settings’ also shows Covid is striking a diverse selection of workplaces, with exposure and not personal frailty or circumstances the standout similarity. Mail delivery had 148 workplace outbreaks, construction sites 160, first responders 218, distributors and transporters 408, retailers 559, offices 687 and manufacturing 1,082.

An 11 February 2021 paper on Covid-19 risk by occupation and workplace from the SAGE EMG Transmission Group noted: "Within sectors that have remained active during lockdown, evidence shows that people who work in some specific occupations and roles have increased risks of being infected, hospitalised or dying prematurely. This is higher in many occupations where people have to attend a workplace compared with people in occupations who can work from home (high confidence)."

SAGE added: “Requiring more people to come to a workplace is likely to increase the risk of transmission associated with that workplace (high confidence). People attending the workplace while unwell (more likely if not provided with sick leave or financial compensation) increases the risk of transmission in the workplace.”

It reiterated: “Occupations that are less likely to be able to work from home have higher Covid-19 mortality rates than those that can work from home (high confidence).”

If you were in a predictably risky job it came with a predictably high risk of dying. If you worked from home and were in a professional grade with greater autonomy over how and where you worked, regardless of all other accidents of birth you did not.

Source: ONS, 25 January 2021.

Source: ONS, 25 January 2021.

Not serious enough

HSE’s Enforcement Management Model (EMM) sets a high bar for a ‘serious’ problem at work, this consequence descriptor requiring a condition to cause “a permanent progressive or irreversible condition, causes permanent disabling leading to a lifelong restriction of work capability or a major reduction in quality of life.” Outside of the HSE abnormal lexicon, that would be more likely to be labelled ‘devastating’ or ‘catastrophic.’

HSE’s calculation is not based on evidence that too few die for Covid-19 to be considered ‘serious’, but that too many survive.

On a dedicated webpage explaining HSE’s position, it notes: “The reason why HSE decided the impact of the pandemic does not justify the use of the ‘serious’ category is because, unlike other life-threatening health risks such as asbestos, it does not affect workers in exactly the same way. We are acutely aware that workers have died following a positive Covid test and for some workers it is a very serious condition, which may have long-lasting consequences. However, for many workers, symptoms may be very mild.”

DEATH ANGER UCU expressed its concern at the ‘appalling’ loss of a Burnley College teacher to Covid-19. Donna Coleman, a longstanding UCU member who worked with vulnerable students at Burnley College, died aged 42 on 6 January 2021. The union had earlier raised concerns about the college’s ‘poor Covid controls’. UCU general secretary Jo Grady said: “We are all angry and devastated about the loss of Donna,” adding: “Too many workers, including those in post-16 education, have lost their lives to Covid. These deaths are not inevitable.”

There is certainly a low risk of an individual of working age suffering a Covid-19 infection going on to die. But because so many have been infected, a low risk translates to large numbers. Even according to the figures reported to HSE by employers, there were 367 work-related Covid-19 deaths in less than a year, and over 30,000 reported cases. In any normal discourse, a recorded work-related death toll running at three times last year’s workplace fatality total of 111 deaths would qualify as a ‘serious’ problem.

And if ‘serious’ includes severe illness and death, the Covid-related workplace risk for certain jobs undeniably reaches the threshold. An Occupational & Environmental Medicine paper published online in December 2020 looked at the seriousness of Covid symptoms in UK workers. Severe infection was defined as a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19, while in hospital, or death attributable to the virus.

It found compared with non-essential workers, those working in healthcare roles were more than 7 times as likely to have severe infection. Those working in social care and education were 84 per cent as likely to do so; while ‘other’ essential workers had a 60 per cent higher risk of developing severe and sometimes fatal Covid-19.

When the researchers refined the employment categories further, it emerged that medical support staff were nearly 9 times as likely to develop severe disease; those in social care almost 2.5 times as likely to do so; while transport workers were twice as likely.

With the exception of transport workers, for whom heightened risk of severe Covid-19 infection was linked to socioeconomic status, the findings held true even after accounting for potentially influential risk factors, including lifestyle, co-existing health problems, and work patterns.

Seriously, not serious?

HSE’s Sarah Albon said the decision that Covid-19 should not be ranked as 'serious' was “made by a group of very experienced inspectors, scientists and policymakers who would generally keep the EMM up to speed.” The ‘significant’ classification was then endorsed by “one of our senior operational committees.”

But Albon did not tell MPs the whole story. In response to a request for a listing of the biological agents for which HSE has assigned ‘consequence descriptors’ under the Enforcement Management Model, HSE told Hazards the consequence descriptors laid out in its Appendix 2 and 3 of its Enforcement Management Model are informed by Hazard Group rankings determined by another committee, the Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens (ACDP).

The terms of reference of ACDP, a multiagency expert panel, are: “To provide as requested independent scientific advice to HSE, and to ministers through DHSC, Defra, and their counterparts under devolution in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, on all aspects of hazards and risks to workers and others from exposure to pathogens.”

Until 2013 HSE provided the ACDP secretariat. That is no longer the case. The role now falls to Public Health England, but HSE still maintains close links with ACDP. The still current HSE Approved List of biological agents, produced by ACDP and which took effect on 1 July 2013, still carries the HSE brand in its nameplate. And this list exposes a problem with HSE’s lower priority ‘significant’ ranking for Covid-19.

It notes: “The classifications in the Approved List assign each biological agent listed to a hazard group according to its level of risk of infection to humans, where Hazard Group 1 agents are not considered to pose a risk to human health and Hazard Group 4 agents present the greatest risk.”

This most recent, third, edition of the Approved List pre-dates Covid-19, but does rank two coronaviruses, SARS and MERS, in Hazard Group 3, where exposures “can cause severe human disease and may be a serious hazard to employees; it may also spread to the community, but there is usually effective prophylaxis or treatment available.”

Approved List of biological agents, third edition, HSE, 2013.

Approved List of biological agents, third edition, HSE, 2013.

Appendix 2 of HSE’s Enforcement Management Model (EMM): Application to Health Risks defines “serious health effects”, and includes: “Infections due to biological agents in Hazard Groups 3 & 4 and some agents in Group 2.”

Both SARS and MERS have been linked to international outbreaks falling well short of a pandemic, with exposed workers an at-risk group (Hazards 151). HSE has given both of these coronaviruses a ‘serious’ designation, consistent with their listing in Appendix 2.

In a 29 March 2021 email statement, HSE confirmed to Hazards it had given Covid-19 the same classification as its coronavirus cousins. “SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes Covid) is classified as a hazard group 3 biological agent. The COSHH categories for microbiological agents are relevant to roles involving deliberate work with biological agents.”

But despite its own enforcement application rules indicating all Hazard Group 3 and even some Group 2 agents should go into the Appendix 2 list of agents causing “serious health effects”, HSE indicates that when it comes to Covid-19 it is willing to break its own rules and give it a contradictory “significant health effects” classification.

Less deadly, more deaths

The Approved List raises questions about the rules and assumptions underpinning HSE’s classification system. How could HSE take three coronaviruses, put them in the same Hazard Group and give the higher ‘serious’ consequence descriptor to SARS and MERS, each responsible for several hundred deaths worldwide, compared to Covid-19 which has killed over 100,000 people in the UK alone?

An explanation could be that the Approved List is a poor fit, not intended to deal with pandemics where all workers could be at risk. Many of the highest risk jobs for Covid-19 – in food production, retail or transport, for example – were never intended to be within its scope.

Explaining why Covid-19 got the lower ‘significant’ classification, HSE chief executive Sarah Albon told the 17 March 2021 work and pensions committee: “What the classification is recognising is that the likely outcome for a typical healthy workers, thank goodness, is that most people will not go on to suffer permanent or fatal consequences.”

The 2003 SARS outbreak caused around 8,000 cases worldwide, out of which fewer than were 800 deaths, a 1-in-10 risk of death once infected. MERS kills about a third of those infected, but since 2016, there have been just 1,465 cases worldwide and between 300 and 500 deaths. But while both were far more deadly than Covid-19 once a person was infected, neither the SARS nor MERS coronaviruses were anywhere near as transmissible.

Professor Raina MacIntyre, head of the Biosecurity Research Program in the University of New South Wales school of medicine, said this and other factors meant the HSE ‘significant’ classification for Covid-19 could not be justified. The professor, who is a globally respected expert on infection transmission, told Hazards: “Whilst the case fatality rate of SARS CoV 2 is lower than SARS, it is higher than pandemic influenza in 2009 and probably in 1918 (or similar to 1918).

“Other important differences are that people who recovered from SARS had complete recovery – this is not the case for SARS CoV 2, with substantial long term health effects including ‘long-Covid’. Further, SARS CoV 2 directly attacks the heart, so in addition to causing serious lung disease, it can also cause cardiac damage which may be irreversible. The rates of hospitalisation and intensive care unit (ICU) admission are also very high.”

Covid-19 was causing over 1,000 reported workplace infections a week in the UK in January 2021, and has in all probability caused several times more work-related deaths in the UK than SARS and MERS combined caused worldwide.

All three viruses posed a significant occupational risk, but for SARS and MERS this was limited largely to the health care setting. Both were an easier fit for HSE’s ACDP-derived classification system.

In a 26 March 2021 statement regarding the Approved List, HSE told Hazards: “The guidance makes clear that it is for use by people who deliberately work with biological agents, especially those in research, development, teaching or diagnostic laboratories and industrial processes, or those who work with humans or animals who are (or are suspected to be) infected with such an agent in health and animal care facilities.”

This distinction, repeated in the 29 March HSE statement to Hazards confirming Covid’s higher Group 3 classification, is important. Covid-19 just didn’t fit the model. Elevated risks are not concentrated in health care and labs. The January 2021 ONS analysis confirmed both work-related infections and deaths are much higher across a wide range of occupational groups including health and social care, but also to transport, construction, office work, food processing and jobs that couldn’t be done from home. HSE’s own, but now axed, weekly outbreaks updates showed the same pattern.

The chances of an individual infected worker dying was far lower, relative to MERS and SARS. However given the extremely high rates of transmission, the absolute numbers infected or dying from Covid-19 was on a different and much higher scale. HSE’s self-admitted low-ball figure for reported cases had exceeded 30,000 by March 2021, with over 5,700 reported in January 2021 alone. Work-related death notifications reported by employers were approaching 400.

There is no dispute that social factors will always be a major determinant of health. But excesses are in ‘essential’ jobs and remain after correcting for socioeconomic factors. Large excesses of cases and deaths have occurred in sectors where large numbers of outbreaks occurred. The HSE chief said there was “a very complex system at work here” and factors including low pay and shared transport and housing were important risk factors for transmission. But these were all knowns, and were all circumstances driven by employers who set the pay rates driving those circumstances. They were risk factors that should have been accounted for in risk assessments and in HSE’s enforcement response.

There is no question HSE was facing an unprecedented challenge, spanning the scale, complexity and demarcation of regulatory responses. Professor John Simpson, who leads at Public Health England (PHE) on public health guidance for Covid-19, told the work and pensions committee: “One of the things that has been difficult for the Health and Safety Executive is that a lot of workplace outbreaks may be more to do with social factors within the workplace.”

But the workplace is HSE’s turf. It is the main agency with knowledge of workplace processes and laws, a right of entry to workplaces and the power to take regulatory action. When outbreaks happen in the workplace, HSE should know about it and should make available its considerable arsenal of powers to address it. Whether it comes to tracking outbreaks or treating Covid-19 with the priority it deserves, many believe the watchdog has fallen short.

According to infection transmission expert Professor MacIntyre: “This ranking by HSE does not make sense, especially in the UK when over 124,000 people have died from Covid-19. If you look at the risk of dying from an accident on a construction site versus dying from SARS CoV 2, the latter is a much higher risk.”

HSE wasn’t keeping Britain safe. It was keeping Britain working.

Out of control

Hazards has found evidence that rather than establishing a unique Covid-19 specific Enforcement Management Model classification using the Enforcement Management Model (EMM): Application to Health Risks and the Approved List, HSE opted to take Covid-19 out the system it applied to SARS and MERS.

Covid-19 was instead slotted into the enforcement model’s “biological agents” heading for “incidental exposure to micro-organisms,” where these agents are given a blanket “significant health effects” designation. This isn’t a scientifically-derived or health-based designation. It is a catch-all for infections HSE considers troubling, but not that deadly and that are not caused by exposure to substances handled deliberately or encountered when caring for the infected, but which may be encountered incidentally.

Hazards asked HSE for “a listing of the biological agents for which HSE has assigned ‘consequence descriptors’ under the Enforcement Management Model, and those descriptors.” In an emailed statement, the regulator responded: “HSE does not have a list of biological agents with assigned consequence descriptors.” But there must be at list of at least one – HSE had stated to the select committee the case for Covid-19 had been through the process and assigned a ‘significant’ descriptor.

Questioned further by Hazards, HSE issued this 26 March 2021 clarification: “No such listing exists beyond the indicative examples given in the online published EMM guidance Enforcement Management Model (EMM): Application to Health Risks which relates to occupational exposure to conventional health and safety issues.”

Albon confirmed to MPs it would complete a review of Covid-19 classification at the end of April. “Essentially there is a big literature review and a consideration of all this newer scientific evidence that emerged.”

But it was not a paucity of evidence that was the problem. HSE had already assigned Covid-19 a Hazard Group 3 rating, which should have come with an automatic ‘serious’ designation. Workers were dying in droves in certain jobs because those jobs came with a much higher risk of exposure. The problem was the classification system used by HSE was no longer fit-for-purpose. What HSE is treating as an ‘incidental risk’ at work has, in all probability, killed thousands.

Enforcement malaise

“HSE is guilty of policy-based evidence making,” commented Hilda Palmer of the national Hazards Campaign. “It all flows from government, but the HSE just went along, rubber stamping, and mutually reinforcing each other.”

As HSE concocted arguments of convenience to define a pandemic in the workplace as something less than ‘serious’, to fit a narrative decided elsewhere by government, workers were sacrificed. But how HSE decided on its novel, Covid-specific semi-privatised regulatory approach has been a closely guarded secret.

No open meetings of the HSE board have been held since the start of the pandemic, and in a departure from normal practice no agendas, minutes or meeting papers have been posted online.

The minutes of HSE’s two most recent board meetings, obtained by Hazards through a freedom of information request, were so heavily redacted it was impossible to discern anything concrete about how it decided its strategy or the content of that strategy.

There is though troubling evidence of a regulator, forced by circumstance or a lack of will, operating a Covid amnesty and handing over the reins to public health agencies unfamiliar with workplace practices and rules.

HSE has insisted it arrived on its own at a ‘significant’ rather than ‘serious’ risk classification for Covid-19. But in doing so, HSE decided workers must face a significantly increased risk. What HSE delivered was a classification more in tune with the government’s desire to keep Britain working.

HSE has handed over the bulk of its enforcement role to private contractors who are unqualified, without experience in workplace health and safety and without the legal access to workplaces and enforcement powers of qualified and experienced inspectors.

The select committee queried the behaviour of an enforcer that won’t enforce, a regulator that gifted its mandate to public health bodies with no workplace knowledge or powers, and that maintains it is doing a good job despite outsourcing its safety critical on-the-ground role to a debt collectors.

We need an effective, enabled and willing HSE.

It is about time we got one.

TUC survey reveals widespread Covid-Secure failures

The TUC’s latest biennial survey of workplace safety representatives has found widespread Covid-Secure failures. The survey of more than 2,100 workplace safety representatives reveals employer failures on risk assessments, social distancing and PPE during the pandemic.

Key findings of the survey findings on Covid-19 and health and safety at work, include:

Risk assessments More than a quarter of safety representatives said they were not aware of a formal risk assessment being carried out in their workplace in the last two years, covering the period of the pandemic. Almost one in ten (9 per cent) said their employer had not carried out a risk assessment, while 17 per cent said they did not know whether a risk assessment had taken place. Of those who said their employers had carried out a risk assessment, more than a fifth (23 per cent) said they felt the risk assessments were inadequate.

Workplace outbreaks More than threequarters of safety representatives (83 per cent) said employees had tested positive for Covid-19 in their workplace, while more than half (57 per cent) said their workplaces had seen a “significant” number of cases.

Enforcement Less than one quarter (24 per cent) of respondents said their workplace had been contacted by a Health and Safety Executive inspector, or other relevant safety inspectorate in the last 12 months. More than a fifth (22 pr cent) said their workplace had never been visited by an HSE inspector, as far as they were aware.

Social distancing A quarter (25 per cent) of representatives said their employer did not always implement physical distancing between colleagues through social distancing or physical barriers. Just over a fifth (22 per cent) said their employer did not always implement appropriate physical distancing between employees and customers, clients or patients.

Personal protective equipment More than a third (35 per cent) said adequate PPE was not always provided.

Mental health concerns and stress Almost two thirds of safety representatives (65 per cent) said they are dealing with an increased number of mental health concerns since the pandemic began. Threequarters (76 per cent) cited stress as a workplace hazard.

TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady said: “Britain’s safety representatives are sounding the alarm. Too many workplaces are not Covid-secure. If we want to keep people safe, we must stop infections rising again when workplaces reopen.

“Everyone has the right to be safe at work. The government must take safety representatives’ warnings seriously. Ministers must tell the Health and Safety Executive to crack down on bad bosses who risk workers’ safety. And they must provide funding to get more inspectors into workplaces to make sure employers follow the rules.

“Unionised workplaces are safer workplaces, and union safety representatives save lives. We send our thanks to the safety reps across the country for all they are doing to keep working people safe in the pandemic.”

Follow the money

HSE’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic has been severely hampered by a lack of resources. Mike Clancy, the general secretary of Prospect, the union representing health and safety inspectors at the HSE, told the work and pensions committee HSE had suffered cuts of 54 per cent in real terms since 2010, reducing the ability of the organisation to respond to the virus.

Clancy told MPs the vast majority of proactive site visits conducted by the HSE in response to Covid have been by external contractors “such as debt collection agencies” – 52,000 compared to 12,000 carried out by trained HSE inspectors. Two private debt-collection companies – Engage Services (part of Marston Holdings) and CDER Group – were awarded contracts by HSE worth a combined £7m to carry out spot checks on behalf of the regulator.

HSE insisted they were appointed “following all procurement procedures.” However, an HSE source told Hazards there was no open procurement for the work, with the two contracts awarded directly to the firms in September under emergency pandemic rules. Another questioned the role played by the outsourced service, noting “these are not inspections, these are spot checks, with the Spot Check Support Officers giving firm’s a tick-box Covid pass without ever getting past reception.”

Prospect’s Mike Clancy HSE’s resorting to private contractors exposed a “structural lack of capacity in HSE,” which now has only 390 main grade inspectors. He told MPs that a “lesson had to be learned” about the impact of cutting capacity and the inability to turn the tap back on to respond to a crisis.

Speaking after the session, he said: “Smart health and safety regulations require trained expert inspectors with the right tools to do the job. It is an inescapable fact that we don’t have enough people with the right powers to properly enforce these regulations across the economy.

“Government has to change tack and provide a long-term funding settlement to HSE. This is the only way to restore inspector numbers and boost the confidence of businesses, workers and consumers that health and safety at work is something we take seriously as a country.”

Fetter conceit

It is part of a body of evidence suggesting HSE’s definition of ‘serious’ may have been, if not complacent, seriously ill-advised.

And its own inspectors are clear the ‘significant’ designation took enforcement action largely out of equation. Prospect’s Mike Clancy said HSE’s decision to classify Covid-19 as a ‘significant’ rather that a ‘serious’ risk under its Enforcement Management Model (EMM) had put an effective block on HSE inspectors taking enforcement action for Covid breaches, telling MPs that only it was only “latterly” advice was revised so “prohibition notices are an element that is available.”

He said HSE “should not be shackled in taking the right enforcement action,” adding “the enforcement management code needs to be changed so that this is recognised as a serious risk and that will enable the sort of activity that people are looking for. The paucity of prosecutions here has to be a civic society concern, but it should not be laid at the door of the inspectorate. It is operating within the structures that are given to it.”

The HSE leadership demurred. Both Albon and HSE director of field operations Samantha Peace told the committee that throughout the pandemic its inspectors had been free to take enforcement action. Both it seemed were working off the same crib sheet.

Albon emphasised “absolutely nothing in that enforcement management model fetters the ability of our inspectors to take the appropriate enforcement action in the light of any issue they see.”

Peace told MPs: “Nothing has fettered us from taking whatever the range of enforcement action is that we feel is appropriate given the facts before us, the circumstances.”

That just turned out to no prosecutions. And while over 20 per cent of pre-pandemic concerns resulted in an enforcement notice, that figure for Covid-19 concerns dropped to less than 0.2 per cent.

HSE is more than 100 times more likely to take action if the concern doesn’t concern Covid-19 at work.

‘Something has gone badly wrong’

New research from the Institute of Employment Rights (IER) has found strong evidence that risk was not sufficiently mitigated in workplaces because Covid-19 rules were not adequately enforced.

“When the pandemic was declared on 11 March 2020, the government had to decide how it would balance the protection of public health with the protection of the economy,” said Phil James, a professor of employment relations at Middlesex University and editor of the thinktank’s March 2021 report. “A year later, our analysis suggests it got that balance wrong.”

He added: “Our jobs are among the most important features of our lives, but they are not worth our lives, nor are they worth the lives of colleagues, family and friends. This light-touch approach to the regulation of businesses during the worst pandemic we have seen in 100 years must now be subject to a major independent public inquiry to understand what went wrong and how we can do better. It is vital that we learn from the failings of workplace regulation over the last year, because this pandemic proves that workers' health is also public health – it benefits us all.”

Lord John Hendy QC, chair of the IER and a co-author of HSE and Covid at work: A case of regulatory failure, said: “Something has gone very badly wrong when enforcement action has been taken against tens of thousands of members of the public and holidaymakers are threatened with 10 years in jail but employers known to have put thousands of people at risk are getting off scot free.

“There has been health and safety legislation on the UK's statute book for over 200 years. The current regulations are well known and could have been reasonably and effectively applied to protect workers. They were not. Had employers been reminded of their legal duties and these laws enforced through robust inspections and effective penalties, workplaces could have been made a lot safer than Covid-19 has shown them to be."

HSE and Covid at work: A case of regulatory failure, IER, March 2021.

The smoking gun

Piecing together information from disparate HSE reports, a picture of an occupational risk classification dangerously unfitted to rating Covid-19 becomes apparent. The result is the risks from Covid-19 at work were downplayed and the enforcement response was inadequate, with risks not effectively mitigated.

Enforcement Management Model (EMM) – had no way to take account of the concentration of Covid-19 risks in a range of essential jobs, or the impact of millions of infections nationwide on workplace infection rates and fatalities. For example, SARS is classified as a ‘serious’ risk, because if 10 people were infected in a workplace, one might be expected to die. If Covid-19 infected over 500 in a workplace, then you might expect at least one to die. So one SARs death and 10 infections is classified under the HSE model as ‘serious’ but one Covid-19 death and 500 infections is not. This isn’t theory. Over 500 workers were infected at the DVLA office in Swansea, and at least one has died.

Enforcement Management Model (EMM): Application to Health Risks - describes the Hazard Group systems related to the serious/significant system, from group 1 (safe) to 4 (deadly). All 3 and 4 are definitely classified as serious, some 2s are. HSE stresses “it is for use by people who deliberately work with biological agents”. Most high risk jobs for Covid-19 fall outside this category.

The Approved List of biological agents - MISC208(rev2) – gives Hazard Group classifications for biological agents. Puts MERS and SARS in a ‘serious’ 3 group, because fatality rates once infected are high. On 29 March 2021, HSE confirmed to Hazards that Covid-19 had also been given a Hazard Group 3 ranking. An automatic consequence descriptor of ‘serious health effects’ should have followed. This happened for SARS and MERS. But for Covid-19 HSE, unexplained, decided on downgrading the consequence descriptor to ‘significant’.

RUBBED OUT

It was not a good time for the workplace safety regulator to take a back seat. But Hazards editor Rory O’Neill reveals how the Health and Safety Executive, faced with thousands of reported workplace outbreaks and hundreds of Covid-19 deaths, deferred to public health agencies, outsourced investigations and went on an enforcement holiday.

| Contents | |

| • | Introduction |

| • | Serious concerns |

| • | On the record? |

| • | Outbreaking bad |

| • | Not serious enough |

| • | Seriously, not serious? |

| • | Less deadly, more deaths |

| • | Out of control |

| • | Enforcement malaise |

| Other stories | |

| • | TUC survey reveals widespread Covid-Secure failures |

| • | Follow the money |

| • | Fetter conceit |

| • | ‘Something has gone badly wrong’ |

| • | The smoking gun |

| Hazards webpages | |

| • | Hazards news |

| • | Infections |

| • | Work and health |

See the dedicated Hazards coronavirus resources pages.

See the dedicated Hazards coronavirus resources pages.