Dangerous lead

Hazards special report, November 2009

Stop press! HSE withdraws lead safety guide after Hazards exposes “reckless” advice [more]Using never before published data, Hazards can reveal tens of thousands of workers are at risk of kidney and heart disease, brain damage, cancer and other serious disorders at the UK’s ‘safe’ workplace lead exposure limit.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) figures published online in March 2009 show 8,069 workers were under medical surveillance for lead exposure in 2007/08 [1]. HSE sets a recommended action level of 50 micrograms of lead per 100ml of blood (µg/100ml – sometimes expressed as µg/decilitre (dl)) for men and 25 µg/100ml for women. Suspensions from work with lead are required if the levels hit 60 µg/100ml and 30 µg/100ml respectively. However, recent evidence has revealed workers are at risk of hypertension, kidney and brain damage, reproductive harm and cancer at levels a fraction of these official limits, as low and possibly lower than 10 µg/100ml.

Poisoned by lead in UK workplaces

Paint me a picture East European migrant workers renovating a Scottish mansion suffered acute lead poisoning in 2008, some requiring hospital treatment. They had been sanding down paints in the historic building, which had gone virtually untouched for a hundred years. Full case history

Surgical examination Working out of GPs surgeries, occupational health specialist Simon Pickvance has seen a regular stream of workers suffering serious health problems as a result of exposure to lead. Many of the cases, though, had not been linked to lead at work or notified to the authorities. And some of the workers in the most dangerous jobs for lead exposure often go for years without a blood test, he says. Full case history

Follow my lead When over 150 workers on a Liverpool construction site complained of lead poisoning symptoms, the company took immediate action. It followed two of the workers to a union office and to a blood testing clinic, then laid them off. Bosses from Colebrand admitted they had tracked the whistleblowers, but denied this had anything to do with them losing their jobs as painters and labourers. Full case history

The unpublished internal HSE figures obtained by Hazards, showing the precise levels of lead exposure measured by the safety watchdog, reveal for the first time that around 5,000 workers, known to have blood lead levels below the UK action thresholds but above 10 µg/100ml, could be suffering potentially deadly lead related ill-health.

Many thousands more, who have previously been exposed to lead and who may now be retired, could also be affected, as research shows lead-related health effects caused by cumulative exposure may only emerge in old age.

There is a better way

In Washington State, USA the official SHARP Adult Blood Lead Surveillance (ABLES) programme defines occupational lead overexposure as a blood lead level greater than or equal to 25 µg/100ml, a level that sets off no alarm bells for the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

The state’s Department of Labor and Industries’ ABLES programme offers consultation to employees and employers with cases at this level and above. The statistics suggest this system is far more effective than the UK equivalent.

In the UK, over 8.6 per cent of those monitored by HSE in 2007/08 were found to have blood lead levels at or above 40 µg/100ml. By contrast, Washington State’s ABLES surveillance programme records very few cases reaching this level. In fact, in 2008, 99 per cent of cases in Washington State were less than 25 µg/100ml. This success has been attributed to the dissemination of prevention materials at the individual case level and targeted prevention strategies for high exposure risk industries.

The Washington State action level means employee exposure to an airborne concentration of lead of 30 micrograms per cubic metre of air (30 µg/m3) and employers shall assure that no employee is exposed to lead at concentrations greater than 50 micrograms per cubic metre of air (50 µg/m3). The UK regulations and code of practice don’t consider there’s a problem until airborne lead levels are at least twice the Washington limit.

Medical surveillance must be provided to all employees exposed at any time above the action level. The employer shall remove an employee from work when the employee's blood lead level is at or above 50 µg/100ml – compared to the UK level of 60 - and may be returned after two consecutive blood sampling tests indicate that the employee's blood lead level is at or below 40 µg/100ml.

Each employee whose blood sampling and analysis indicates a blood lead level at or above 40 µg/100ml, must have repeat sampling at least every two months until two consecutive blood samples and analyses indicate a blood lead level below 40 µg/100ml.

SHARP lead programme • ABLES annual update 2009 [pdf] • Washington Administrative Code (WAC) and rules on medical removal from work

Research by Hazards has revealed not only that the current UK exposure standards are leaving lead-exposed workers at a real risk of disabling and potentially life-threatening disease, but that existing lead poisoning notification and industrial disease benefit rules are entirely inappropriate and ineffective.

The official approach to lead at work ignores over a decade of evidence of harm caused by levels a fraction the UK standard, and the reporting and benefits structure is unsuited to modern patterns of exposure and lead-related disease.

But while many nations, including France and Germany, have a tighter standard, HSE has told Hazards is has “no intention” of reviewing the current UK standard. And it is not acting in ignorance. A key HSE advisory panel on chemical risks discussed evidence of potentially life threatening risks at lower levels and recommended the standard be reviewed.

The UK had got not just one of the most lax blood lead standards around, it’s got one of worst occupational exposure limits for lead at work. This means HSE allows more lead in the workplace air which, combined with the less onerous biological limits, creates a situation where more poisonings are allowed to occur and less action is likely to be required to remedy the problem.

A growing problem

Lead is not a problem that is going away. Globally, lead production has increased dramatically [2]. And the UK still produces hundreds of millions of tonnes of refined lead every year, with production increasing in recent years [3]. Consumption, of course, is much higher as much of lead reaching the UK in batteries and other products is sourced from outside the UK.

There are no reliable figures on the numbers exposed to lead at work in the UK. But a 2007 occupational cancer report for HSE [4] gave a figure of 65,000 workers for workplace lead exposures categorised as “higher”.

This is an artificially depressed figure. The authors discounted numbers employed in ‘iron and steel foundries’, assuming these largely overlapped with ‘foundry workers’. In fact lead exposures have occurred in lots of metal related trades outside of foundries, for example wire drawing.

A “higher” exposures figure, anyway, will miss most of those exposed to lead, who will either have lower levels of lead in workplaces of the type known to HSE, or will entirely unquantified lead levels because they work in industries in the mobile, casual, grey or entirely illegal economy beyond HSE’s reach.

Others are in jobs that employ relatively small numbers – for example making dog combs, model making, firing range staff, jewellers, wheel balancers, cable jointers, fluorspar miners and processors, archaeologists handling lead coffins, workers recycling electronic equipment – but could involve significant exposures. Add all these jobs to the total and it could push the numbers potentially at risk from occupational lead exposure into the hundreds of thousands.

Some of those overlooked by HSE could be precisely the workers facing the highest exposure risks. A 2004 study of blood lead levels in US workers found the highest prevalence of levels above 10 µg/100ml was among construction labourers (12.5 per cent), followed by vehicle mechanics (9.1 per cent) and construction trades people [5].

Among US workers with lead levels above 25 µg/100ml, construction labourers again topped the list, with 7.3 per cent having this level and above, compared to just 0.28 per cent in the category “production workers: machine operators, material movers.”

In the UK, construction labourers are at best employed on sites of limited duration; at worst they are migrant and informal workers invisible to the authorities – so their exposures and their symptoms go entirely unseen.

These workers are almost entirely off HSE’s radar. Although HSE separates out “demolition” in its breakdown of lead exposed groups, it doesn’t even identify construction workers as one of the principal at risk categories.

Table 1: Blood lead levels measured in exposed male workers 2007/08

Click on table for larger version • Source: HSE, 31 March 2009.

Table 2: Blood lead levels measured in exposed female workers 2007/08

Click on table for larger version • Source: HSE, 31 March 2009

The internal HSE breakdown obtained by Hazards reveals blood lead levels that will be causing lead-related disease. Not that you’d know this from official occupational disability statistics or the legally required notification system for cases of occupational lead poisoning.

Hazards reviewed the Department of Work and Pensions quarterly Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit statistics from the December 2002 to the June 2008 report, the most recent figures available. Only one quarterly report, June 2004, recorded workers had been assessed for poisoning by lead (prescribed disease C1), when five cases were assessed. The outcome of these assessments was not given, but this means that no more than five workers in the last six years have received lead-related industrial disease benefits, and possibly none. This suggests the system is failing to reach workers suffering lead-related poisoning symptoms and, even if it does, those assessments would be too limited to pick up the range of problems now known to be associated with even low level lead exposures.

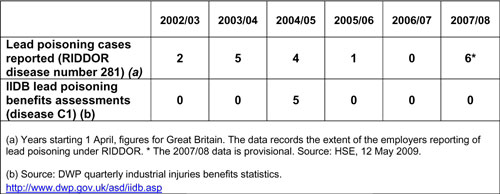

Cases of lead poisoning must be notified to the authorities under the RIDDOR regulations. However, unpublished RIDDOR figures obtained by Hazards show reports hit a six year high of six cases in 2007/08, with only one case reported in the preceding two years combined (see Table 3).

Table 3: Lead poisoning notifications and benefits assessments

What is apparent from these figures is that the notification and benefits system related to lead poisoning is not appropriate for monitoring and compensating the types of lead related disability which is affecting workers at levels at or below the current UK action limit of 50 µg/100ml. The limit should be tightened and the benefits and notification rules revised to recognise the harm caused at these lower blood lead levels.

But Hazards has discovered HSE, despite internal papers showing it is aware of evidence showing potentially deadly health risks below the current standard, is even ignoring advice from its own advisory panels recommending the standard is reviewed.

In fact, correspondence on the issue has been bouncing for several years between HSE’s Advisory Committee on Toxic Substances (ACTS) and its sub-committee, the Working Group on Action To Control Chemicals (WATCH) [6] [7] [8] [9]. Concerns raised by, among others, the head of HSE’s Corporate Medical Unit, did not appear to inject any urgency into the proceedings.

A review of the occupational lead standard, agreed in 2002 and scheduled for 2006, is still to occur. Meetings of HSE committees in 2008 again agreed a review of the evidence for a new, tighter standard was needed, but nothing happened.

Then everything went quiet from November 2008. The minutes of that ACTS meeting were as of 1 November 2009, a year on, still under wraps. But, after repeatedly acknowledging the need for a review of the lead standard, HSE in October 2009 told Hazards “there is no intention to review the lead standard at this point in time.”

It has not only fallen off the agenda. There isn’t even a meeting of the ACTS committee scheduled on whose agenda it might appear.

• We should, but we won’t - the full story of HSE's failure to act on lead warnings

Low levels, high risks

‘Indecent exposure’, report published in March 2009 by a health research centre at the University of California, Berkeley [10], notes: “As scientific evidence has shown more serious health effects associated with lower lead levels than previously anticipated, the number of persons who must be considered at risk increases dramatically.” The UC Berkeley report concludes that even at very low levels – much lower than the US and UK exposure limits – workers are at risk of heart and kidney problems and decreased brain function and reproductive problems.

HSE’s bad lead on lead

A 2009 comparison of lead exposure standards in 20 countries revealed the UK had the worst occupational exposure limit for airborne lead, twinned with one of the worst for allowable blood lead levels in workers.

The Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists positions paper the indicates the UK occupational exposure limit of 0.15mg/m3 for lead in workplace air is three times the permissible level in Argentina, Austria, Bulgaria and Denmark. The UK had among the highest permissible blood lead levels for males. Its action level of 50 µg/100ml and suspension level of 60 µg/100ml compares to a blood lead limit of 20 µg/100ml in Denmark, which had the most protective standards listed.

AIOH recommends a 30 µg/100ml “blood lead transfer level” for males and females not of reproductive capacity and 10 µg/100ml for females of reproductive capacity.

This is in line with the recommendation of European Union’s Scientific and Social Committee for Occupational Exposure Limits (SCOEL). Its initial recommendation, published in September 2000, was to lower the applicable exposure limits throughout Europe to 30 µg/100ml.

Inorganic lead and occupational health issues, AIOH Position Paper, AIOH Exposure Standards Committee, March 2009.

Evidence has shown than the supposedly safe workplace standard is far from safe, and many of those with ‘low’ blood lead levels are in fact developing serious, permanent and sometimes life-threatening conditions as a result.

This is not even news - evidence on low level exposures to lead and increased risk of hypertension and stroke has been cited in standard occupational health textbooks since the mid-1990s, for example Rosenstock and Cullen’s 1994 Textbook of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (pages 747-749).

The complacency of the UK authorities about low level exposures has ensured lead related disease is far more widespread and serious than the UK authorities care to admit.

There is also some evidence that those facing some of the highest exposures may be missed by the formal exposure monitoring system. This could include workers employed informally or in scrapyards recycling lead others sometimes handling illegally stripped lead, workers unaware they are removing or grinding structures covered with lead based paints and workers scrapping or reconditioning old televisions or computers.

According to the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition: “Many older TV and computer monitors can contain up to 4-8 lbs of lead. It is also used in the soldering on the circuit boards. Exposure can cause brain damage, nervous damage, blood disorders, kidney damage and developmental damage to fetus. Children are especially vulnerable. Acute exposure can cause vomiting, diarrhoea, convulsions, coma or death.” [11]

It’s the use of lead in the electronics industry that explains one other worrying statistic. Globally, use of lead is increasing.

The British Geological Survey’s (BGS) 2009 ‘World Mineral Production 2003-2007 [2] shows a marked year-on-year increase in refined lead production worldwide over the period, up 18 per cent from 6.9m tonnes in 2003 to 8.1m tonnes 2007.

The UK still uses considerable amounts of lead, the BGS report shows. UK production of refined lead has varied over the period, with a high of 364,574 tonnes in 2003, dropping to a low of 245,938 tonnes in 2004. It rose significantly in 2005 and 2006 to above the 300,000 tonnes mark, before slipping back to 263,391 tonnes in 2007. The UK’s contribution to the amount of occupational lead exposure, though, extends beyond this domestic production. Consumption is considerably higher, with lead imported in products manufactured overseas, from batteries to computers. Mountains of electronic equipment are exported as waste for “recycling”. Some of the waste is scrapped, and some recycled. Both processes inevitably lead to a lead hazard.

The BGS report lists top global uses of lead in 2008 as lead-acid batteries (80 per cent), pigments (5 per cent), rolled extrusions (6 per cent), shot/ammunition (3 per cent), alloys (2 per cent) and cable sheathing (1 per cent).

A March 2007 BGS mineral factsheet [3], produced jointly with UK government, showed a steady increase in consumption of lead in the UK from 2003 to 2005, up from 305,400 tonnes to 330,000 tonnes.

Table 4: Production of refined lead

The UC Berkeley team is calling for the revision of OSHA standards – which are broadly similar to the existing UK standards - and recommends measures including eliminating unnecessary uses of lead, substituting safer compounds, and expanding education and outreach for employers and workers. “Clearly, current workplace standards are not protecting workers and their families from unsafe lead exposure. Ignoring the mountains of evidence is no longer an option,” said Holly Brown-Williams, one of the report authors. “Health problems caused by lead can, and must, be prevented.”

Prison labour exposed to deadly toxins

Staff and inmates at a US prison industry computer recycling plant worked without protection against exposure to high levels of lead and cadmium. When the problem was discovered, however, the amount of health damage or risk could not be assessed because the Elkton Federal Correctional Institution in eastern Ohio did not conduct medical monitoring or industrial hygiene surveillance.

However, a July 2008 report from the US government's National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) found staff and inmates were exposed to concentrations of lead and cadmium far above permissible limits in Elkton's industry computer recycling plant. The plant was subsequently shut down. NIOSH found “there was no respiratory protection used or any type of engineering control in place to minimise exposures” and there was no medical monitoring of inmates or staff.

PEER news release. Full NIOSH report [pdf]. AFGE statement [pdf].

The call has been backed by Dr Philip Landrigan, an expert on lead toxicity at New York's Mount Sinai School of Medicine. “The continuing overexposure of American workers to lead and the persistent occurrence of occupational lead poisoning is a national scandal,” he said.

This mirrored the findings of an April 2007 report from the US Association of Occupational and Environmental Clinics, which concluded “the evidence for adverse effects at levels of exposure far below those currently permitted by OSHA speaks forcefully for an immediate reduction in permissible exposures in the workplace.”

The Berkeley report warned that blood levels of lead less than 20 µg/100ml can cause hypertension, a risk factor for heart disease, stroke and chronic kidney damage. Impaired kidney and brain function can occur below the HSE limits, the report indicates.

A 2003 report in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine [12] looked at levels below the US occupational exposure standard of 50 µg/100ml. It found “gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal and nervous system symptoms increased with increasing blood lead levels. Nervous, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal symptoms all began to be increased in individuals with blood leads between 30-39 µg/100ml and possibly at levels as low as 25-30 µg/100ml for nervous system symptoms.”

The paper notes: Approximately 70 per cent of individuals with blood lead levels at 50 µg/100ml or below “responded they had been bothered by symptoms involving either the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or nervous system for the past 3 months before the interview.”

Any acknowledgment of these low level effects is entirely missing from the HSE approach, which instead concentrates on the now extremely rare cases of acute lead poisoning causing symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, irritability, stomach pains, nausea, constipation and weight loss. Its ‘Lead and you’ guide [13] claims: “Serious health problems rarely occur unless people people have at least 100 micrograms” of lead in their blood. In fact, heart and kidney disease, brain damage and other effects have been found at much lower levels, sometimes with the disability only emerging years after exposure when the blood lead levels will have subsided but the cumulative body dose will still be having an effect.

Employers, even major employers, seem uncertain about the law and unaware of the risks at relatively low blood lead levels. Laing was the main contractor on a job where over 150 workers complained of poisoning by lead (see case history).

Papers for a November 2006 Network Rail conference on railway bridges included a contribution from another construction giant, Balfour Beatty Civil Engineering, on the topic of the 'Forth Bridge - safety and production'. It notes that the removal of the original lead paint was carried out in accordance in the Control of Lead at Work Regulations (CLAW) and Network Rail standards. It adds: "All persons who may come into contact with lead working must be subject to a monitoring of blood level concentration which is carried out by a Medical Practitioner or body approved by HSE. There is a statutory trigger level of 70 milligrams of lead per 100 millilitres of blood, at which level HSE must be notified."

In fact the level referenced in the Balfour Beatty article is a nonsense, because there is not a specific HSE reporting trigger limit. Worse still, lead levels in blood a fraction that cited by Balfour Beatty would in all probability have seen all its workers dead. It is over 1,000 times higher than the HSE action limit for workplace lead of 50 micrograms of lead per 100 millilitres of blood (µg/100ml) and the 60 µg/100ml suspension limit. HSE's US equivalent, OSHA, notes that "studies have associated fatal encephalopathy" with blood lead levels as low as 150 µg/100ml. It adds other forms of disease have been observed in workers “with blood lead levels well below 80 µg/100ml.”

In November 2009, HSE removed the Lead and You leaflet from its website.

This suggests two things. Firstly, HSE is conceding its leaflet is overly complacent on health risks and is not-fit-for-purpose; and secondly, the only information HSE produced for a lay audience on lead risks at work has now been removed from the website. Instead of providing complacent information for the lead exposed workforce, it is now providing no information at all.

• Stop press! HSE withdraws lead safety advice

Inaction limits: Health risks from low level lead

While only 260 workers were found to be above the HSE action limits and just 29 workers were suspended from work in 2007/08 because their blood lead level exceeded the 60 µg/100ml suspension level, that doesn’t mean these were the only workers potentially at risk.

The unpublished internal HSE figures obtained by Hazards giving a breakdown of blood lead levels for all those under medical surveillance show 5,015 workers in 2007/08 had blood lead levels above 10 µg/100ml, and out of these 3,207 workers had blood lead levels in excess of 20 µg/100ml. In total, 699 had exposures in excess of 40 µg/100ml. All these workers had levels of lead in their bodies the US report identified as presenting a risk of permanent health damage. The UK and US lead surveillance figures are not directly comparable, but do suggest if anything the UK has proportionally more workers with high levels of blood lead.

Brain damage

The 2009 Berkeley report notes: “Decreased brain function in adults has been associated with blood lead concentrations of 20 to 50 µg/100ml.” In 2007/08, official surveillance identified over 3,000 UK workers with blood lead levels at or above 20 µg/100ml and over 250 of these had lead levels at or above 50 µg/100ml.

The UK and US occupational standards are based on monitoring lead levels in the blood of exposed workers, then removing workers from exposure if they exceed certain thresholds, until their blood lead levels have subsided. This is a flawed approach. While blood lead levels may fall this does not mean the risk has been removed, because cumulative exposures can create an ongoing risk. A US study in 2007, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, reported these cumulative exposures in a group of older US adults, measured by lead levels in bone – where lead can be stored for decades – was associated with decreased performance on test of hand-eye coordination and perception (14).

A 2009 US report in the journal Neuropsychology confirmed people exposed to lead at work are more likely to exhibit damaged brain function as they get older, due to this cumulative exposures effect (15). The researchers found both the developing brain and the aging brain can suffer from lead exposure. For older people, a build-up of lead from earlier exposure may be enough to result in greater cognitive problems after age 55.

In this study, the researchers followed up on the 1982 US Lead Occupational Study, which assessed the cognitive abilities of 288 lead-exposed and 181 non-exposed male workers in eastern Pennsylvania. The lead-exposed workers came from three lead battery plants; the unexposed control workers made truck chassis at a nearby location. Both groups were subjected to a battery of tests that evaluated psychomotor speed, spatial function, executive function, general intelligence and learning and memory.

Among the lead-exposed workers, men with higher cumulative lead had significantly lower cognitive scores. This association was more significant in the older lead-exposed men, of at least age 55. Their cognitive scores were significantly different from those of younger lead-exposed men even when the researchers controlled for current blood levels of lead. In other words, even when men no longer worked at the battery plants, their earlier prolonged exposure was enough to matter, the authors concluded.

“Increased prevention measures in work environments will be necessary to reduce [lead exposure] to zero and decrease risk of cognitive decline,” they said.

A 2009 paper looking at low level lead exposures in women, published in Environmental Health Perspectives, concluded “cumulative exposure to lead, even at low levels experienced in community settings, may have adverse consequences for women’s cognition in older age.” (16)

Cardiovascular disorders

The Berkeley report notes that lead exposure “has been consistently associated with increases in blood pressure in studies conducted in both workers and the general population. Several studies have combined data from prior research, and many more of these studies have included workers whose blood lead levels were under 20 µg/100ml, which was still associated with increases in blood pressure.” In 2007/08, over 3,000 UK workers had their blood lead levels measured at or above this level.

UK lead standard poses major heart risk

Exposure to lead over a lifetime has been linked to an increased risk of dying from heart disease by new research. The authors of the US study call for a tightening of the country’s occupational exposure standard – which at 40 µg/100ml of lead in blood is already significantly tighter than the UK male action level of 50 and suspension level of 60.

The researchers, whose finding were published online by the journal Circulation on 8 September 2009 [17], analysed lead concentrations in the blood and bones of 868 men in the Boston area. The men, whose average age was 67 at the start of the study, had lead concentrations in their blood and the bones of the patella (kneecap) and tibia (shin) measured over a nine-year period.

They found that men who had the highest concentrations of lead in their bones had a six times greater chance of dying from cardiovascular disease than men with the lowest concentrations. Men with the highest levels of lead had a 2.5 times greater chance of dying from all causes than men with the lowest levels.

“Cumulative exposure to lead, even in an era when current exposures are low, represents an important predictor of cardiovascular death,” said study author Marc Weisskopf, an assistant professor of environmental health and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

“The findings with bone lead are dramatic. It is the first time we have had a biomarker of cumulative exposure to lead, and the strong findings suggest that it is a more critical biomarker than blood lead.”

A 2006 US study observed that individuals with a blood lead level of 10 µg/100ml or greater had a 60 per cent higher relative risk of death from heart disease than those who had blood lead levels less than 5 µg/100ml. Over 5,000 UK workers had blood lead levels at or above 10 µg/100ml in 2007/08

(18).

Two other papers in 2006 also linked relatively low lead exposures to a higher rate of heart disease. A report in the medical journal Circulation found blood lead levels “generally considered safe” may be associated with an increased risk of death from many causes, including cardiovascular disease and stroke. [19]

Researchers studied lead levels below 10 µg/100ml - this level is a fifth the current UK action level for all male workers, and just one sixth the level where medical suspensions are required.

The researchers used data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Mortality Follow-Up Study, involving 13,946 adults whose blood lead levels were collected and measured between 1988 and 1994. When researchers studied those who died by 31 December 2000, they found that death from any cause, cardiovascular disease, heart attack and stroke increased progressively at higher lead levels. The levels studied are common and considerably lower than lead levels perceived by the US government as a concern to public health, said Dr Paul Muntner, author of the study and an associate professor of epidemiology and medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans.

In a separate study of South Korean workers published in the journal Epidemiology, Dr Barbara S Glenn, from the US government's Environmental Protection Agency and colleagues found that blood pressure responds relatively quickly to changes in lead levels [20]. The study involved 575 people in South Korea who had worked for an average of 8.5 years in a job that exposed them to lead. The researchers measured lead levels and blood pressure in the subjects, whose average age was 41, from October 1997 to June 2001. The authors found that as lead levels changed on a yearly basis, so did blood pressure. They concluded this suggests that it is not just the cumulative lead dose over a lifetime that influences blood pressure.

Kidney function

Low to moderate levels of lead exposure have been associated with adverse changes in kidney function, the Berkeley report concluded. It says the association may be even worse in people who have other risk factors for kidney disease, such as hypertension – itself caused by low level lead exposures – or diabetes. Related conditions include nephritis and nephropathy.

Cancer

In 2006, the United Nations’ International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded: “Inorganic lead compounds are probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A).” [21] There is no safe level for exposure to a carcinogen – and lead has been linked to brain, central nervous system, kidney and other cancers.

A 2006 study concluded people who are routinely exposed to lead at work are 50 per cent more likely to die from brain cancer than people who are not exposed. The University of Rochester Medical Center study was based on information from the US Census Bureau and the National Death Index. The findings, published in the International Journal of Cancer, computed the risk estimates for lead exposure and brain cancer from a census sample of 317,968 people who reported their occupations between 1979 and 1981 [22].

The study found the death rate among people with jobs that potentially exposed them to lead was 50 per cent higher than unexposed people, and the number of deaths was larger than in many previous studies. Scientists have suspected for years that lead is a carcinogen, which passes through the blood-brain barrier, making the brain especially sensitive to the toxic effects of lead.

Epidemiologists concerned at lax lead standards

The US-based Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) has recommended a change in the case definition of elevated blood lead levels in adults. In a vote at the CSTE’s June 2009 conference in Buffalo, the organisation approved a proposal to consider blood lead levels of 10 micrograms per 100 millilitres (µg/100ml) or more in adults as “elevated.”

The current UK action level for blood lead in male workers is 50 µg/100ml, with workers not suspended until the level hits 60 µg/100ml. UK safety watchdog the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) maintains health effects are not normally seen below 80 µg/100ml, adding that serious effects “rarely occur” below 100 µg/100ml. But CSTE says studies show that blood lead levels as low as 10 µg/100ml contribute to an elevation in blood pressure and attendant health risks, including stroke. It adds that low blood lead levels also are associated with an increase in mortality from heart disease, decreased kidney function and changes in cognition (mental performance).

CSTE president Mel Kohn said: “While we often think of lead poisoning as a health concern in children and pregnant women, we need to address how lead poisoning is affecting adults, from exposure in the workplace and from hobbies such as target shooting.” CSTE says the risk of lead poisoning is especially pronounced among workers in certain industries including lead refining and smelting, construction work involving paint removal, demolition and maintenance of outdoor metal structures such as bridges and water towers, and battery manufacturing and recycling.

CSTE • Earth Times • Sun Herald

Reproductive risk

Reproductive risks to both male and female workers exposed occupationally to lead have been long recognised. Low to moderate levels of lead exposure during pregnancy have been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and with harmful effects on fetal physical growth and brain development, the Berkeley report notes.

It points to two prominent studies in which the average maternal blood lead level during pregnancy was approximately 10 µg/100ml or less that found prenatal lead exposure was associated with decreased childhood IQ.

A 1993 substance datasheet from the US government’s health and safety watchdog, OSHA, notes: “The blood lead levels of workers (both male and female workers) who intend to have children should be maintained below 30 µg/100ml to minimise adverse reproductive health effects to the parents and to the developing fetus.”

Although the current UK standard has a suspension limit of 30 µg/100ml for women, designed to protect their reproductive health, there is no equivalent standard to protect the reproductive health of men, with the general suspension level twice the US recommendation.

Urgent action is required

The UK blood lead levels obtained by Hazards reveal the existing UK standard is inadequate and is leaving thousands of workers at risk. These data provide the evidence-base for significant tightening of the UK exposure levels.

The Health and Safety Executive’s expert committees have time and again recommended the UK standard be revisited. A review scheduled for 2006 has not materialised; subsequent decisions to require a review have been quietly forgotten or dismissed.

Occupational lead poisoning has been a notifiable disease in the UK since 1896. Yet again we have an example of an old hazard remaining with us; the control standards necessary to reduce the very serious and multiple risks to human health from lead have not yet been adopted. We have failed to learn the lessons of history on this threat and a rapid remedy is now needed.

Key action points

• Eliminate all unnecessary uses of lead; where lead is used ensure use is minimised and ensure best engineering and other controls are used.

• Revise the HSE standard to recognise the health risks of low level exposures and low blood lead levels.

• The DWP’s industrial injuries benefits rules and RIDDOR notification rules covering workers affected by lead must be revised to recognise the harm caused at these lower blood lead levels.

• Recognise the cumulative health risk posed by lead, which may cause its worst effects in older workers, including retired workers.

• Investigate the extent of exposures to lead in workplaces not currently under official surveillance.

• Improve HSE education and information materials and outreach work to improve awareness of lead related problems at work and their avoidance.

• Launch a parliamentary investigation into the failure of HSE to follow through decisions of its advisory committees and the dysfunctional nature and lack of urgency displayed by the committees’ themselves.

• Prosecute all employers who negligently expose workers to lead.

| Main occupations with a lead risk Workers are at risk from lead in industries from construction, to plastics manufacture to metal processing. Medical surveillance of lead-exposed workers occurs most commonly in the following industries. • Smelting, refining, alloying or casting • lead battery industry • Manufacture of inorganic and organic lead compounds • Painting of buildings and vehicles • Scrap industry • Glass making • Manufacture of pigments and colours • Potteries (glazes and transfers) • Ship repair and ship breaking • Badge and jewellery enamelling • Civil engineering renovation work US government occupational health research body NIOSH says the following occupations are among those where workers may be exposed to lead: • Cable splicing • Construction • Manufacturing: - bullets - ceramics - ceramic tiles - electrical components - lead batteries - pottery - stained glass • Mining • Painting • Radiator repair • Recovery of gold and silver • Repair and reclamation of lead batteries • Smelting • Welding • Work on firing ranges |

References

1. HSE lead exposure figures for 2007/08, published online March 2009.

2. World Mineral Production 2003-2007, British Geological Survey, 2009. [pdf]

3. Metals: Mineral Planning Factsheet, British Geological Survey, March 2007. [pdf]

4. The burden of occupational cancer in Great Britain, Research Report RR595, HSE, 2007.

5. AS Yassin and others. Blood lead levels in US workers, 1988-1994, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, volume 47, number 7, pages 720-728, July 2004.

6. Minutes of the ACTS meeting, 25 May 2007 [pdf].

7. Minutes of the WATCH meeting, 17 June 2008 [pdf].

8. Minutes of the WATCH meeting, 23-24 October 2008 [pdf].

9. Agenda of the ACTS meeting, 11 November 2008. As of 1 November 2009 the minutes were not available.

10. Indecent exposure: Lead puts workers and families at risk, Perspectives, volume 4, number 1, March 2009 [pdf]. www.healthresearchforaction.org.

11. Toxins in electronics, Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition (SVTC).

12.KD Rosenman and others. Occurrence of lead-related symptoms below the current Occupational Safety and Health Act allowable blood lead levels, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, volume 45, number 5, pages 546-555, May 2003.

13. Lead and you - a guide to working safely with lead, HSE leaflet INDG305. The leaflet was removed by HSE from its website in November 2009; it had been posted at http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/indg305.pdf The leaflet can now be viewed on the Hazards website [pdf].

14. RA Shia and others. Cumulative lead dose and cognitive function in adults: A review of studies that measured both blood lead and bone lead. Environmental Health Perspectives, volume 115, number 3, pages 483-492, 2007 [abstract].

15. Naila Khalil and others. Association of cumulative lead and neurocognitive function in an occupational cohort, Neuropsychology, volume 23, issue 1, pages 10-19, 2009 [abstract]. APA news release.

16. Jennifer Weuve and others. Cumulative exposure to lead in relation to cognitive function in older women, Environmental Health Perspectives, volume 117, number 4, pages 574-580, 2009.

17. Marc G Weisskopf and others. A prospective study of bone lead concentration and death from all causes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer in the Department of Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study, published online before print 8 September 2009 [abstract] • Harvard University news release

18. SE Schrober and others. Blood lead levels and death from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Results from the NHANES III mortality study, Environmental Health Perspectives, volume 114, number 10, pages 1538-1541, 2006.

19. Andy Menke and others. Blood lead below 0.48 µmol/L (10 µg/dL) and mortality among US adults, Circulation, volume 114, issue 13, pages 1388-1394, September 2006 [abstract]

20. Barbara S Glenn and others. Changes in systolic blood pressure associated with lead in blood and bone, Epidemiology, volume 17, number 5, pages 538-544, September 2006 [abstract].

21.Inorganic and organic lead compounds. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, volume 87, 2006.

22. Edwin van Wijngaarden and Mustafa Dosemeci. Brain cancer mortality and potential occupational exposure to lead: Findings from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study, 1979-1989, International Journal of Cancer, volume 119, issue 5, pages 1136-1144, 2006 [abstract]. University of Rochester news release

Resources

HSE working with lead webpages

HSE statistics on workers exposed to lead

NIOSH lead webpages, USA

Substance Data Sheet for Occupational Exposure to Lead - 1926.62 App A, OSHA, USA, 1993.

The Lead Group, Australia

Poisoned by lead in UK workplaces

House renovation poisons workers

The renovation of a multi-million-pound Scottish mansion ground to a halt in 2008 after several workers were struck down with lead poisoning. Some of the workers required hospital treatment.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) issued a 9 September 2008 improvement notice on work at the baronial mansion of Findynate Estate near Strathtay. Work stopped while HSE undertook an investigation. HSE’s improvement notice said the work was in breach of the Control of Lead at Work Regulations 2002 (CLAW).

The building had remained virtually untouched since it was remodelled around 100 years ago and still containing historic features such as original William Morris wallpaper. The work started in September 2008 after Blairish Restorations Limited won the £800,000 contract to “completely modernise and renovate” the category B-listed, 10-bedroomed property.

James Woolnough, managing director of Blairish Restorations, said he had been “gobsmacked” when his workers fell ill. “This is a completely unique building, last decorated in 1907.Our guys were sanding down paint finishes and ingested the dust from the sandings. Unfortunately some became ill,” he said.

Lead paint is common in older buildings, and a risk assessment should have identified the problem and resulted in safe work methods. Under CLAW, if an assessment finds that exposure of employees to lead is likely to be "significant", the employer must introduce specific controls such as issuing employees with protective clothing, carrying out air monitoring and placing them under medical surveillance.

HSE improvement notice, 9 September 2008.

Not what the doctor orders

Working out of GPs surgeries, occupational health specialist Simon Pickvance has seen a regular stream of workers suffering serious health problems as a result of exposure to lead. Many of the cases, though, had not been linked to lead at work or notified to the authorities.

“I have met a leaded steel melter with wrist drop (undiagnosed) and appalling gums though no lead line by the time I met him, and several lead burners with knackered chests but almost certainly more vascular damage than could otherwise be explained,” Mr Pickvance told Hazards. He said the current medical surveillance system is failing workers. “I’ve seen a lot of people who had blood leads twice in a working life time in the scrap industry or elsewhere. This still happens. I have no faith in Health and Safety Executive (HSE) figures - they may show the right shape of decline because lead uses are probably better controlled than 30 years ago but certainly not the right scale.”

Brian, one of the patients advised by Mr Pickvance, had recently moved to a new job at a leaded steel manufacturer. “When he had his initial blood lead test, his result was surprising - his blood lead was already raised at about 35 µg/100ml. It turned out that his last job had been at a PVC window manufacturer. Until forced by the EU to remove these compounds PVC extrusions contained lead compounds to prevent them from degrading. The exposure is not well-known and even now, as the PVC industry tries to show its environmental credentials by recycling more, it may not be over.”

Keith, another patient seen by Simon Pickvance, was a plumber all his working life. “He was one of the best - a bit of a perfectionist - and always asked to take charge of the awkward lead welding needed on leaded roofing. He would describe welding lead tanks, bending his head into the semi enclosed space to do it,” Mr Pickvance told Hazards. “There were only two blood leads recorded in his medical records - but enough to show that he had been overexposed. The reason he came to see me was that when he retired he found he couldn't enjoy his hobbies the way he had hoped - he used to go to the theatre and opera.

“His attention span was poor and his memory was shocking. I tried to help him to claim disablement benefit for lead poisoning: inevitably the claim went to appeal and was heard by doctors who clearly knew less about lead poisoning than we did. But there was a kind of justice in the end. We reported his lead poisoning to HSE and to his old employer. Keith found out afterwards, the firm had completely revamped safety practices for working with lead. His employer never admitted the reason though.”

Bosses tracked workers to clinic

Two labourers were laid off after bosses kept watch on them as they went for health checks for possible lead poisoning, following roof stripping work at Liverpool’s Lime Street Station. Colebrand area manager Neil Kershaw admitted he had been outside a union office office with supervisor Frank Locco, and had also followed Peter Donnelly and his colleague Peter Standeven to a clinic where blood tests were being carried out.

The Colebrand managers, who were subcontracted by Laing to do the painting and lead-related work on the station renovation, denied this had anything to do with them being laid off from their jobs as painters and labourers. Mr Donnelly had earlier asked the firm for a blood test. He said he was laid of because he had raised safety concerns.

Mr Donnelly and Mr Standeven had both worked at Lime Street station throughout 2000 stripping lead-based paint from the roof. Both had suffered illness including weight loss and vomiting. Mr Standeven had been suspended from all lead-based duties in October 1999, after his levels reached dangerously high levels.

Colebrand was hired by construction giant Laing to strip lead-based paint from the roof of Lime Street station as part of a £16m facelift in January 1999. At places, the lead-based paint was estimated to be half an inch thick and to date back to the Victorian era.

An estimated 175 workers claimed their health had been affected by lead exposures on the Lime Street job. The project's scaffolding subcontractor Rigblast almost doubled the value of its original £3.5m contract due to stoppages. Among reasons cited by Rigblast was the need to avoid high levels of lead in the air, which led to work being suspended on six occasions.

Bridge workers poisoned by lead

Dozens of workers on the Auckland Harbour Bridge in New Zealand were poisoned after inhaling lead-based paint dust during maintenance work in 2008. The men, who took off their full-face dust masks because they were uncomfortable to work in, were among the 315 people known to have suffered lead poisoning throughout New Zealand that year.

The blood lead levels of about 50 men working on the bridge project were monitored by their employer, and within a month of beginning work, up to half of them showed marked increases. They had been involved in stripping metal in tunnels on the underside of the bridge, most of which was painted in the 1950s when paint routinely contained lead. Those affected were sweeping up contaminated paint dust. Although they had been provided with full-face masks, the men found them uncomfortable and replaced them with less effective dust masks that they wore over their hooded overalls. It meant the masks were being taken off before the workers had removed their contaminated clothing, allowing them to inhale the dust.

A Labour Department spokesperson said officials remained concerned about the health effects of lead in paint, even though it was regarded as an historical problem.

We should, but we won’t

Minutes of the May 2007 meeting of HSE’s Advisory Committee on Toxic Substances (ACTS) [6] record that a trade union member of the committee “suggested that a review of the Control of Lead at Work Regulations 2002 (CLAW) should be considered to take account of recent epidemiological evidence linking exposure below current limits with increased heart disease and strokes.”

By June 2008, the issue had been bounced to the Working Group on Action To Control Chemicals (WATCH) sub-committee [7], the meeting’s minutes noting: “On lead, concerns have been raised at ACTS about recent evidence that blood levels of lead of the order of 10 µg/100ml may be associated with cardiovascular disease. Give that all of the recent published literature relating to this issue has not been fully surveyed, ACTS considered that a systematic literature search was needed and suggested that this could be carried out by HSE. It was envisaged that such a review would inform on the need to pursue a revision of exposures limits for lead.”

The meeting chair said discussions within HSE had indicated the UK could not unilaterally adopt a new standard, as standards were “now regulated by EU legislation.”

The comment appeared to cause consternation, not least from HSE’s own medical adviser. Dil Sen, a doctor and head of HSE’s Corporate Medical Unit, “reminded WATCH that at the time ACTS had last reviewed lead (in 2002), an undertaking had been given to re-visit the issue in 4 years, but this had not yet happened,” the minutes record. “He pointed out the blood lead suspension levels in some EU countries (eg. France and Germany) are lower than in the UK and this had come about by national regulatory initiatives. He highlighted that the issue of health risks posed by exposure to lead was an important, high profile issue that had received some media attention.”

The minute concludes with agreement that a paper on the topic should be presented to the October 2008 WATCH meeting.

At that October 2008 meeting [8] the chair notes “that studies in the published literature suggested that adverse health effects might be associated with exposures to lead at levels below the current UK regulatory standards. ACTS had asked if there was a need to conduct an updated review of the toxicological profile of lead and lead compounds, leading to a reconsideration of appropriate risk management standards in the UK occupational context.”

In response, a WATCH member, the minutes note, indicated “concerns about neurological effects at blood lead levels of 40 μg/100ml, together with data on reproductive health effects, suggested that the current action level of 50 μg/100ml for workers other than young persons and women may be too high and a lower level, more in line with the current scientific evidence may be more appropriate.” Another WATCH member “noted that there seemed to be evidence that there might be an association between blood lead levels of 10 μg/100ml and increased cardiac and stroke mortality.”

Another pointed to “subtle physiological effects have been linked to exposure levels lower than current occupational exposure guidelines. This raised questions about the level of protection and caution that should be incorporated into control levels for lead. Traditionally, such standards have been based on clinical effects, but it might be that more subtle effects should also be taken into account in the derivation of limits,” the minutes say.

In the light of the discussion, “The Chairman asked WATCH if it considered that it is appropriate for HSE to re-visit the UK regulatory limits for lead? WATCH members signified their agreement” [HSE’s emphasis]. Confirming the decision once more, the chair noted: “WATCH had recommended that the UK standard for lead should be revisited.”

ACTS met a month later, in November 2008 [9]. By 1 November 2009 the minutes of the meeting were still to be posted on the HSE website. An October 2009 request to HSE for copies of the minutes was refused because the minutes were not yet ready. However, HSE did confirm the issue was discussed at the November 2008 ACTS meeting and added: “I'm told there is no intention to review the lead standard at this point in time.”

In response to a request for further clarification, HSE said: “At the ACTS meeting held on 11 November 2008, it was agreed that HSE and ACTS needed to consider revisiting the UK standard on lead. Nothing has yet gone to the Board and there is no immediate plan to review the lead standard.”

HSE confirmed there had been no meeting of ACTS in 2009 and there were no meetings of ACTS scheduled.

HSE has demonstrated a lack of urgency on this issue that amounts to extreme recklessness with the public health of a significant number of workers in the UK. A promised review of the lead standard scheduled for 2006 has yet to occur. Two committees have over a period of at least three years discussed evidence that the UK lead standard could be, at the very least, leaving workers at risk of neurological disorders and heart disease. They have agreed a review of the standard is needed.

But HSE has “no intention” to undertake the review and no meetings scheduled where it could even discuss the issue.

Back to main story

Stop press!

HSE withdraws lead safety advice

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has withdrawn advice on the dangers of working with lead after this Hazards magazine investigation found the watchdog greatly under-estimated health risks that could be affecting over 100,000 workers.

The Hazards article said the official health and safety warnings about the dangers of lead were so complacent the watchdog was guilty of “extreme recklessness” with workers’ health. The current UK maximum exposure limit for males is set at 60 microgrammes of lead in 100ml (µg/100ml) of blood, at which level workers must be suspended until their blood lead level falls.

But the Hazards report, ‘Dangerous lead’, points to substantial scientific evidence that much lower levels - as little as 10 to 20 (µg/100ml), a fraction the current UK standard - can cause chronic, long-term ill health. ‘Lead and you’, HSE’s main guidance for workers on the issue, takes a different line.

It says: “Serious ill-health problems rarely occur unless people have at least 100 microgrammes of lead per decilitre of blood.” After publication on 6 November 2009 of the Hazards report, HSE admitted the leaflet is misleading and has since removed it from the HSE website.

In an HSE statement, the watchdog said the guide would be replaced, adding the new version “will take into account the latest scientific developments and the language used to be clear about risks.”

For now, though, the exposure standard remains unchanged. In October 2009, despite a series of recommendations from HSE expert committees that the lead standard should be reviewed in the light of evidence of risks significantly below the currently permitted exposure levels, HSE told Hazards it had “no intention” of doing anything about it.

However, in November 2009, after publication of the Hazards report and the evidence it presented about risks a fraction the UK permissible workplace standard, sources within HSE have indicated HSE will now revisit the standard.

Dangerous lead

Contents

• A growing problem

• Low levels, high risks

• Inaction limits

- brain damage

- cardiovascular disorders

- kidney function

- cancer

- reproductive risk

- dangerous jobs

• Urgent action is required

- key action points

• References

• Resources

Poisoned by lead

House renovation poisons workers more

Not what the doctor orders

more

Bosses tracked workers to clinic more

Bridge workers poisoned by lead more

Stop press! more

Hazards webpages

Chemicals