Two young women. Two deaths by hanging.

Their May 2023 inquests found both took their own lives when they could no longer cope with pressures at work.

KASEY BROWETT, 25. A coroner said the community care officer killed herself as a result of the “cumulative pressures” of her job.

Kasey Browett, 25, was found dead at her Lincolnshire home on 1 July 2022. The community care officer took her own life when the “cumulative pressures of her employment became too great,” an inquest at Boston Coroner’s Court found.

Coroner Paul Cooper recorded a verdict of suicide into the Lincolnshire County Council employee’s death. The Record of Inquest stated: “The deceased died on July 1, 2022, at Chamomile Way, Spalding, when the cumulative pressures of her employment became too great for her and despite extensive medical treatment she was unable to cope and took her own life.”

Olivia Perks, 21, was found in her room at Sandhurst military college on 6 February 2019. The “positive and bubbly” officer cadet fell victim to a “complete breakdown in welfare support” during her training, an inquest at Reading town hall heard.

OLIVIA PERKS, 21. The officer cadet killed herself after what the coroner said was a “complete breakdown” in support during her training.

Coroner Alison McCormick recorded a conclusion of suicide. She said: “There was a missed opportunity by the chain of command to recognise the risk which the stress of her situation posed to Olivia and a medical assessment should have been, but was not, requested.”

The coroner added: “It is not possible to know what the outcome would have been had a medical assessment taken place, but it is possible that measures would have been put in place which could have prevented Olivia's death.”

Both deaths were undeniably work-related. Even so, neither death was investigated by the workplace health and safety regulator, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

HSE refuses to investigate or record work-related suicides, so work-related causes may not be addressed and the deaths do not appear in work fatality statistics.

The deaths of Kasey and Olivia are not the only recent suicides falling into this HSE-bypassed work-related category.

In two cases – Vaishnavi Kumar and Jaden Francois-Esprit – subsequent independent reports were highly critical of workplace practices and called for changes at work (Hazards 160).

In Jaden’s case, a London Fire Brigade (LFB) commissioned review found “ingrained” prejudice against women and routine racist abuse. A Prevention of Future Deaths report send to LFB by the coroner said it had the power to take preventive action and should do so.

The independent rapid review after the suicide of Vaishnavi concluded there was “a culture that is corrosively affecting morale” at University Hospitals Birmingham (UHB).

A third, Ruth Perry’s suicide, led to intervention by the government to change punitive Ofsted accountability systems (see: Campaign forces school inspection changes).

Despite the government move and “a groundswell of criticism” that prompted a select committee inquiry, HSE again said “it would not follow-up this matter” and told Hazards Ruth’s suicide “could not be reported” as a work-related death.

The job is to blame

Evidence of the association between preventable workplace factors and suicides is not hard to find.

RUTH PERRY, 53. The highly regarded headteacher killed herself while waiting the for her school’s Ofsted downgrading to ‘inadequate’ to be made public.

A June 2023 PLOS ONE study found approximately one in ten NHS healthcare workers in England experienced suicidal thoughts during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, with one in 25 saying they had attempted suicide for the first time, There was a clear correlation with ‘modifiable’ workplace risk factors, the Bristol University led research found.

Another June 2023 paper, published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, found substantial evidence that nursing professionals, especially women, are at a higher risk of suicide than the general public as a result of heavy workloads, bullying, understaffing and feeling ill-prepared to do their jobs.

The team from Oxford University, who examined 100 papers on suicide risks in nurses, found occupational issues appear to have both direct and indirect influences on suicide risk, “perhaps supported by evidence showing suicide rates are lower around retirement age.”

The finding came after a mental health charity warned in April 2023 that hundreds of nurses tried to take their own lives in 2022, with many feeling at ‘a point of no return’ amid intense pressures and burnout.

The Laura Hyde Foundation (LHF) said its data revealed a dramatic increase in the number of nurses attempting suicide in the past two years. It said some 366 nurses are known to have tried to take their own lives in 2022, a 62 per cent increase from 226 in 2020. Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show 482 nurses took their own lives between 2011 and 2021 in England.

LHF, set up in memory of Royal Navy nurse Laura Hyde, who died by suicide in 2016, also said unrelenting pressures, soaring living costs, poor working conditions and bullying are playing a part in the decline of nurses’ mental health.

Construction is another area where elevated suicide rates have been a concern for years.

Glasgow Caledonian University researchers reported in December 2022 that their analysis of ONS figures established the suicide rate for construction occupations in England and Wales in 2021 was 33.82 per 100,000, up from 25.52 per 100,000 in 2015.

They found the suicide rate among workers in the sector had increased for a fifth year in a row, with workers in the sector nearly four times more likely to take their own life compared to other sectors.

The ONS statistics reveal 507 construction workers killed themselves in 2021, up from 483 in 2020.

Workers die, HSE lies

In 2021, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) made a clear statement that work factors could be responsible for suicides (Hazards 156).

SCHOOL LESSONS The government has agreed to reform the Ofsted inspection regime following the stress-induced suicide of headteacher Ruth Perry. The Education Select Committee has launched an inquiry. But HSE has refused to investigate.

A new HSE suicide prevention webpage acknowledged: “Employers have a duty of care to workers and to ensuring their health, safety and welfare. HSE promotes action that prevents or tackles any risks to worker’s physical and mental health, for example due to work-related stress.

“These risks can lead to physical and/or mental ill health and, potentially, suicidal ideation, intent and behaviour. As an employer, there are things you can do to reduce the risk of work contributing to the causes of suicide.”

Since then, HSE has put itself through contortions to argue incorporating work-related suicide in its remit – through requiring reporting of cases and by investigating cases and risks – is impossible. It told Hazards: “Suicides in the workplace, or where potentially linked to work factors, are not reportable to HSE under Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (RIDDOR) as they do not result from an accident, as defined in those regulations.”

It is a flaky and internally contradictory defence for inaction. It is also a lie.

RIDDOR gives this simple definition: ‘“work-related accident” means an accident arising out of or in connection with work.’

A clarification notes: that ‘“accident” includes an act of non-consensual physical violence done to a person at work.’

But there is no explicit exclusion of suicides anywhere in the law itself. This wasn’t a decision of parliament, it was a choice made by HSE. [Story continues below box]

Why HSE has got it wrong

There is no exclusion of work-related suicide reporting in the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (RIDDOR).

The relevant RIDDOR regulation, regulation 6, notes: “Where any person dies as a result of a work-related accident, the responsible person must follow the reporting procedure.”

An explicit rejection of suicides comes only in HSE’s guidance on the types of ‘reportable injury’. It notes: “All deaths to workers and non-workers, with the exception of suicides, must be reported if they arise from a work-related accident, including an act of physical violence to a worker."

The exclusion of suicides was HSE’s choice, disregarded its duty to oversee all the risks arising from employment that cause harm to workers. Further, the definition of 'accident' HSE chooses to use is muddled and inconsistent. A death resulting from ‘an act of physical violence’, which is explicitly included in RIDDOR’s scope and which HSE will investigate, is no more an ‘accident’ than a suicide.

And many workplace deaths and injuries are successfully prosecuted by HSE, which requires the regulator to establish a criminal breach of safety duty. Some involve deliberate criminal acts – removal of a guard, not providing essential safety equipment, putting profits or production before safety – so are not by any rational definition ‘accidents’, but the foreseeable consequences of employer negligence. Like at least some work-related suicides.

RIDDOR notes: “In these Regulations, any reference to a work-related accident or dangerous occurrence includes an accident or dangerous occurrence attributable to –

(a) the manner of conducting an undertaking;

(b) the plant or substances used for the purposes of an undertaking; or

(c)the condition of the premises used for the purposes of an undertaking or any part of them.”

This includes how an employer runs their business, which manifestly can affect mental health and suicide risks.

Nor are ‘accidents’, however defined, the only work fatalities reportable under RIDDOR. A range of occupational diseases are reportable – including frequently fatal diseases caused by exposures to carcinogens or biological agents – despite none being the result of an ‘accident’.

HSE has argued suicides are multifactorial and ‘complex’, making attribution to work and reporting difficult. The same applies to many cases of cancer, asthma and strain injury, all of which are reportable. The defining feature is that there should have been exposure to a work-related risk.

HSE’s US and French counterparts, which both require reporting of work-related suicides, set criteria determining which cases should be reported.

HSE could do the same. HSE’s position is a choice.

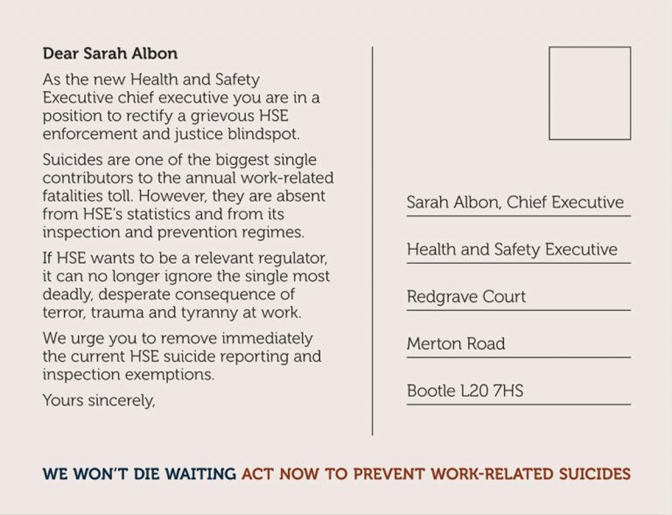

ACTION! Send an e-postcard to HSE demanding it recognise, record and take action to prevent work-related suicides. www.hazards.org/hsesuicide

ACTION! Send an e-postcard to HSE demanding it recognise, record and take action to prevent work-related suicides. www.hazards.org/hsesuicide

Even if there was a legal obstacle to reporting – which there is not – HSE had previously had no problem amending the regulations to suit its purpose. In April 2012, HSE introduced a highly contentious change to RIDDOR, with reporting of most non-major injuries required only after over seven days off work, rather than over three days. The reportable diseases list was truncated too.

In 2023, HSE has investigated zorb incidents affecting members of the public and pesticide residues on food. It’s definition of work-related can be remarkably flexible.

Suicide is only untouchable because HSE doesn’t want to touch it.

Shortsighted watchdog

There is a big and embarrassing problem for HSE. Its own figures show work-related stress, depression and anxiety is at an all-time high in Great Britain and now makes up around half of all work-related ill-health.

The world outside of the HSE leadership’s anaesthetised bubble, including public health professionals and the workers on the receiving end, accepts suicide can be the most desperate manifestation of that harm.

Warning that workplace stress is at “epidemic levels”, the TUC, teaching and other unions have all called for HSE to investigate work-related suicides. TUC head of safety Shelly Asquith said: “It is vital that work-related suicides are reported and investigated by the HSE.”

Professors Martin McKee from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Sarah Waters from the University of Leeds, writing in the British Medical Journal in May 2023, stated that the regulator “must investigate every work-related suicide.”

These HSE probes should take place “in whichever sector they occur and ensure that work-related suicides are subject to the same requirements for reporting and prevention as other occupational deaths,” they stated.

Criticising the explicit exclusion of suicides from HSE’s reporting requirements, they note: “Whenever events at someone’s work seem to be linked to their suicide, it is reasonable to expect that everyone involved will want to find out what happened and how a similar event can be prevented from happening again.”

Jon Richards, assistant general secretary at UNISON, said: “Stress, bullying and harassment at work take a massive toll on the mental health of staff. The HSE should take account of the full impact of work on employees. That includes where workers tragically take their own lives.”

SUICIDE ACT Six simple measures could make action to recognise, record and prevent work-related suicides more effective. more

Unite said allowing HSE inspectors to investigate all work-related suicides is “particularly important in tackling the excessive deaths occurring in industries such as construction.”

The union’s general secretary, Sharon Graham, said: “The failure to fully investigate the reasons why workers in all sectors are taking their own lives is a scandal.

“Until all aspects of why workers commit suicide are investigated, the necessary reforms needed to save lives cannot be implemented.”

Unite national officer for construction Jason Poulter said: “Construction suicide rates are increasing dramatically and the critical issues that are causing workers to commit suicide are not being addressed. The vast majority of construction employers do not take the mental wellbeing of their workforce seriously and until the HSE is given the powers and the resources to investigate these tragedies properly that will continue to be the case.”

Commenting on suicides in health care, Prof Phil Banfield, the chair of the British Medical Association, said: “The HSE must have the necessary resources and correct processes in place to ensure that they can effectively investigate and evaluate this in a way that can result in much-needed change within the healthcare system to ultimately help reduce the prevalence of work-related suicides.”

Hope for the future

HSE is out of touch. It is in denial.

We know workplace stress is out of control. We know that has consequences, and in the most desperate circumstances that will include suicide. HSE’s arguments for inaction are a shameful mixture of evasion and lies. They are a betrayal of its legal mandate.

Its mission statement starts with an unequivocal claim: “HSE's mission is to prevent death, injury and ill-health in Great Britain's workplaces - by becoming part of the solution.”

When it comes to work-related suicides, HSE is not part of the solution. It is, increasingly, the problem.

The time for waiting patiently for HSE to step up is over. The situation for many workers is desperate. They deserve urgency. Their lives depend on it.

References

- Prianka Padmanathan and others, Suicidal thoughts and behaviour among healthcare workers in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study, PLOS ONE, First published online, 21 June 2023 [open access].

- Samantha Groves, Karen Lascelles, Keith Hawton. Suicide, self-harm, and suicide ideation in nurses and midwives: A systematic review of prevalence, contributory factors, and interventions, Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 331, 15 June 2023, Pages 393-404, ISSN 0165-0327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.027

- Sarah Waters and Martin McKee. Ofsted: a case of official negligence?, BMJ, volume 381, page 1147, 21 May 2023. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p1147.

Campaign forces school inspection changes

The government has conceded the Ofsted inspection system must change, in response to a campaign following the suicide of headteacher Ruth Perry after she was told her school would be downgraded (Hazards 161).

In changes given a lukewarm welcome by unions – which are demanding a more fundamental rethink of the schools grading system – Ofsted will revisit schools graded inadequate over child welfare within three months, and there will be an overhaul of its complaints system.

Education secretary Gillian Keegan said the changes announced on 12 June 2023 were “a really important step” and that Ofsted was right to continue to “evolve” to raise school standards.

Ruth Perry’s sister, Prof Julia Waters, who has spearheaded the reform campaign, said the changes were a “step in the right direction” to ensure other headteachers were not put under the “intolerable pressure” her sister had faced.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary at school leaders’ union NAHT, said “it is regrettable that it is has taken a tragedy of this nature for the government to finally realise that reform of school inspection is required.” He added: “This announcement must open the door to immediate and meaningful change agreed with the profession.”

NEU joint general secretary Dr Mary Bousted said the measures “do not go nearly far enough to address the deep concerns of teachers and leaders about the surveillance model of school inspection in England.”

Community national officer Helen Osgood said “there must be an end to one-word outcomes” and NASUWT general secretary Dr Patrick Roach said problems arising from “the crude grading system” still needed to be addressed.

GMB said the system needed “major reforms” after its survey of teaching assistant members revealed 70 per cent had worked extra hours in preparation for an inspection, with 87 per cent unpaid for the extra hours.

On 13 June 2023, the Commons Education Select Committee announced an inquiry into the Ofsted system, with chair Robin Walker noting there had been a “notable groundswell of criticism.”

These workers deserved better

Suicide cases covered in Hazards in the last two years include:

Chloe English, 24. Call centre worker. Jumped to her death from a bridge, after suffering worsening work-related stress and anxiety (Hazards 155).

Linda Salmon, 56. Supermarket worker. Killed herself two days after being signed off work with anxiety because of her fear of catching Covid at work (Hazards 156).

Kevin Clark, 49. Ex-road sweeper. Suffered depression and killed himself two years after being unfairly dismissed (Hazards 156).

Simon Pick, 37. Hotel bar worker. Killed himself four days after he was fired from his job, as a result of problems related to his alcohol dependency (Hazards 156).

Richard Morris, 52. Diplomat. A coroner ruled he killed himself after suffering “severe and acute stress” after working long hours with little time off (Hazards 157).

Wayne Mason, 49. Engineering worker. Killed himself at work when he was supposed be on sick leave with mental health difficulties (Hazards 160).

Vaishnavi Kumar, 35. Hospital doctor. Coroner concluded work stress was a contributory factor in her suicide (Hazards 160).

Owen Vaughan Morgan, 44. Government lawyer. Coroner said he killed himself as a result of “acute” mental health problems related to work stress (Hazards 160).

Jaden Francois-Esprit, 21. Firefighter. Killed himself after racist bullying. Coroner called for his fire service employer to take action to prevent future deaths (Hazards 160).

Ruth Perry, 53. Headteacher. Killed herself while waiting the announcement of a damning Ofsted regrading, despite the school performing well in all but one category assessment (Hazards 161).

Kasey Browett, 25. Community care officer. Coroner said she killed herself as a result of the “cumulative pressures” of her job.

Olivia Perks, 21. Officer cadet. Killed herself after what the coroner said was a “complete breakdown” in support to help her deal with the stress she experienced during training.

Making work suicides count

Six simple measures could make action to recognise, record and prevent work-related suicides more effective.

- Count them Make work-related suicide reportable under the RIDDOR regulations and improve communication between the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and coroners on potential work-related suicide notification.

- Define them Suicides caused by or clearly related to work need to be clearly defined. This could include suicide at work, in work clothes or using work equipment or materials, referrals to occupational health or HR for mental health problems, a history of mental health-related sick leave, a pattern of stress-related problems affecting co-workers, evidence from personal documentation, coroners’ inquests, GPs and other health professionals, or family or suicide notes implicating work factors.

- Assess them Investigating and addressing suicide risks should be part of workplace stress risk assessments and stress management strategies.

- Investigate them Work-related suicide and suicide ideation should be included explicitly in HSE’s inspection guidelines. There should be HSE operational guidelines for inspectors on work-related stress, including work-related suicides. Work-related suicide should be added explicitly to the Work-related Deaths Protocol defining cooperative arrangements between HSE, police, prosecutors and other investigating and statutory agencies.

- Prioritise them Suicide meets the requirement for inclusion in HSE’s Matters of Evident Concern and Potential Major Concern (Hazards 155). The Operational Circular to inspectors should be applied to suicides, and trigger HSE investigations into work-related suicides, suicide patterns or evidence of suicide ideation (suicidal thoughts).

- Compensate them. Deaths from work-related suicide should, in line with other fatal work-related conditions like mesothelioma, be eligible for government compensation. Legal guidance should clarify to courts the potential for work-related suicide causation in civil compensation cases.

ONE LAST ACT

They are not accidents. They can’t be counted. It’s complicated. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) is running out of excuses for refusing to act on work-related suicides. Hazards editor Rory O’Neill argues HSE can no longer remain an absentee regulator as bad jobs lead to the worst consequences.

| Contents | |

| • | Introduction |

| • | The job is to blame |

| • | Workers die, HSE lies |

| • | Shortsighted watchdog |

| • | Hope for the future |

| • | References |

| Related | |

| • | Campaign forces school inspection changes |

| • | These workers deserved better |

| • | Making work suicides count |

| Hazards webpages | |

| • | Work suicide |

ACTION! |

|||

| Use the Hazards e-postcard to tell the HSE to recognise, record and take action to prevent work-related suicides. |

|||

They deserved better

Suicide cases covered in Hazards in the last two years include:

Chloe English, 24.

Call centre worker. Jumped to her death from a bridge, after suffering worsening work-related stress and anxiety (Hazards 155).

Linda Salmon, 56.

Supermarket worker. Killed herself two days after being signed off work with anxiety because of her fear of catching Covid at work (Hazards 156).

Kevin Clark, 49.

Ex-road sweeper. Suffered depression and killed himself two years after being unfairly dismissed (Hazards 156).

Simon Pick, 37.

Hotel bar worker. Killed himself four days after he was fired from his job, as a result of problems related to his alcohol dependency (Hazards 156).

Richard Morris, 52.

Diplomat. A coroner ruled he killed himself after suffering “severe and acute stress” after working long hours with little time off (Hazards 157).

Wayne Mason, 49.

Engineering worker. Killed himself at work when he was supposed be on sick leave with mental health difficulties (Hazards 160).

Vaishnavi Kumar, 35. Hospital doctor. Coroner concluded work stress was a contributory factor in her suicide (Hazards 160).

Owen Vaughan Morgan, 44.

Government lawyer. Coroner said he killed himself as a result of “acute” mental health problems related to work stress (Hazards 160).

Jaden Francois-Esprit, 21.

Firefighter. Killed himself after racist bullying. Coroner called for his fire service employer to take action to prevent future deaths (Hazards 160).

Ruth Perry, 53. Headteacher.

Killed herself while waiting the announcement of a damning Ofsted regrading, despite the school performing well in all but one category assessment (Hazards 161).

Kasey Browett, 25.

Community care officer. Coroner said she killed herself as a result of the “cumulative pressures” of her job.

Olivia Perks, 21.

Officer cadet. Killed herself after what the coroner said was a “complete breakdown” in support to help her deal with the stress she experienced during training.