The new law was overdue. Under the Worker Protection Act workers now have for the first time explicit legal protection from harassment at work.

Employers “must take reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment of employees” in the course of their employment, the amendment to the 2010 Equality Act notes.

ACT NOW The TUC says the old system relied on “victim-survivors” to expose sexual harassment at work, risking escalation and victimisation. Now employers have a positive legal duty to make the workplace safe.

ACT NOW The TUC says the old system relied on “victim-survivors” to expose sexual harassment at work, risking escalation and victimisation. Now employers have a positive legal duty to make the workplace safe.

The provisions under the law, which took effect on 26 October 2024, go beyond abuse by managers or coworkers, and reflect union calls for third parties – patients, customers, callers, passengers and other non-workers encountered in the course of doing your job – to be included.

And employers have to have an action plan; there is a proactive duty to have systems in place anticipating and seeking to avoid potential risks.

Unions said employers are now “on notice” to meet a new legal duty to “take reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment.”

Unite general secretary Sharon Graham said: “Although it isn’t perfect, Unite welcomes the new law and is today putting employers on notice that we will be holding them to account if proactive policies to prevent sexual harassment are not in place. Sexual harassment occurs across the economy — strong unions backed by effective legislation are essential for stamping it out.”

Unite national officer for equalities Alison Spencer-Scragg said: “Preventing sexual harassment should be at the top of every employer’s agenda.”

WORKER VOICE Union reps have a critical role to pay in ensuring the new harassment law is effective. “As we know, legislation can be a powerful tool but if it doesn’t translate into action, its impact is limited,” the TUC says.

WORKER VOICE Union reps have a critical role to pay in ensuring the new harassment law is effective. “As we know, legislation can be a powerful tool but if it doesn’t translate into action, its impact is limited,” the TUC says.

TUC general secretary Paul Nowak commented: “The Worker Protection Act is an important step towards making workplaces safer for workers, particularly women, but more needs to be done.

“No-one should face sexual harassment at work, or in wider society, but we know that women experience sexual harassment and abuse on an industrial scale.

“Many women in essential frontline jobs – like shopworkers and GP receptionists – suffer abuse and harassment regularly from clients and customers.”

“The new Act, which was hard-won by unions, will put the responsibility firmly on employers to take a pro-active and preventative approach to keeping workers safe from sexual harassment and to tackling it in their workplaces.”

Who’s looking?

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is the regulatory agency overseeing application of the new law, properly titled the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Act 2023.

EHRC chief executive John Kirkpatrick, said “the Worker Protection Act will introduce new preventive duties for employers regarding sexual harassment in the workplace. We welcome these vital protections coming into force.

“Sexual harassment continues to be widespread and often under-reported. Everyone has a right to feel safe and supported at work.”

The EHRC head added: “The new preventative duty aims to improve workplace cultures by requiring employers to proactively protect their workers from sexual harassment. Employers will need to take reasonable steps to safeguard their workers. We have updated our guidance to ensure they understand their obligations and the kinds of steps they can take.

“We will be monitoring compliance with the new duty and will not hesitate to take enforcement action where necessary.”

Sound good. But EHRC isn’t like the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). In contrast to HSE, EHRC doesn’t have field inspectors undertaking preventive inspections.

It is a proactive law without proactive enforcement.

An EHRC spokesperson told Hazards: “Our enforcement powers, such as carrying out an investigation, can only be exercised where we suspect unlawful conduct has occurred under the Equality Act 2010. We have no legal powers to inspect beyond this.”

So, EHRC can do nothing unless it has reasonable grounds to believe an offence has already been committed. And unlike safety laws enforced by HSE, there is no provision under the harassment act for punitive penalties where employers break the law.

And while HSE can stop work presenting an imminent risk with a prohibition notice, EHRC’s powers are limited to “seeking court injunctions and making findings of unlawful conduct following investigations,” EHRC’s spokesperson said.

“Our legal powers are designed to challenge suspected breaches and, where required, secure compliance with Equality Act 2010 duties through remedial action.

“Those powers can only be used where we suspect unlawful conduct has occurred.”

Financial redress for people who experience unlawful conduct under the Equality Act 2010 is provided through courts and tribunals. To have any chance of legal redress, it is down to affected workers to take an employer to court.

Despite these shortcomings, EHRC says it is the only appropriate enforcer. “The EHRC is Britain’s regulator of equality law. As such, we are the only body with the legal powers to enforce compliance,” it told Hazards.

“Other regulators may however treat sexual harassment in the workplace as a form of misconduct in their work. For example the Financial Conduct Authority’s non-financial misconduct definition covers this type of treatment.”

Harassment hurts

Harassment is by any reasonable definition a health and safety issue at work.

The International Labour Organisation’s Violence and Harassment Convention 2019 (Convention 190) – which the government ratified in June 2022, so should be reflected in UK law – says ILO member states “shall adopt laws and regulations requiring employers to take appropriate steps commensurate with their degree of control to prevent violence and harassment in the world of work, including gender-based violence and harassment, and in particular, so far as is reasonably practicable, to… take into account violence and harassment and associated psychosocial risks in the management of occupational safety and health” (Article 9(b)).

This shall require employers to “identify hazards and assess the risks of violence and harassment, with the participation of workers and their representatives, and take measures to prevent and control them” (Article 9(c)).

The convention adds ILO member states “shall take appropriate measures to… monitor and enforce national laws and regulations regarding violence and harassment in the world of work” (Article 10(a)) and “provide for sanctions, where appropriate, in cases of violence and harassment in the world of work” (Article 10(d)).

C190 also notes member states “in consultation with representative employers’ and workers’ organizations, shall seek to ensure… violence and harassment in the world of work is addressed in relevant national policies, such as those concerning occupational safety and health, equality and non-discrimination, and migration” (Article 11(a)) and shall do this “by means of national laws and regulations, as well as through collective agreements or other measures consistent with national practice, including by extending or adapting existing occupational safety and health measures to cover violence and harassment and developing specific measures where necessary” (Article 12).

C190 says governments that have ratified the convention – including the UK – “shall” meet these requirements. It isn’t guidance, it a binding requirement in international law.

HSE has explicitly excluded harassment from its job sheet. Left to EHRC, the UK does not enforce through sanctions (C190 Article 10(d)) its laws on harassment, instead only providing in the Worker Protection Act for after-the-fact redress for those taking a successful case to tribunal.

This tribunal system is unavailable for breach of the preventive duty alone. Harassment is an outlier when it comes to employer negligence putting workers at risk, as on other issues HSE routinely takes prosecutions where the law has breached – for example on unguarded machinery, electrical hazards, risks from vehicles or falls or poorly controlled chemicals, dust and fumes - but no injury or ill-health has occurred.

UNSAFE UNSEEN Women’s jobs in public service, care and hospitality can leave them at high risk of sexual harassment. Employers now have a legal duty to anticipate and address these risks.

UNSAFE UNSEEN Women’s jobs in public service, care and hospitality can leave them at high risk of sexual harassment. Employers now have a legal duty to anticipate and address these risks.

Sexual harassment at work often involves physical or psychological abuse and has been linked to depression and poor mental health.

It is unquestionably an act of violence, and would fall clearly within the definition used by HSE.

This says “work-related violence” is: “Any incident in which a person is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work.”

HSE adds: “It is important to remember that this can include:

• verbal abuse or threats, including face to face, online and via telephone

• physical attacks

“This might include violence from members of the public, customers, clients, patients, service users and students towards a person at work.”

In 2019, HSE changed its investigation policy three months after it was accused by Hazards of having an ‘enforcement anomaly’ and a ‘prevention blindspot’ on workplace harassment (Hazards 146).

In a move described by the TUC as a ‘significant advance’, HSE amended its official guidance on ‘reporting a concern’ about work-related stress to say it may instigate a safety investigation into bullying or harassment “if there is evidence of a wider organisational failing.”

But in a significant leap backwards, the same webpage has now been amended again. In a #Not Us moment, the safety regulator notes: “HSE is not the appropriate body to investigate bullying or harassment.

“Bullying and harassment, and similar issues of organisational discipline, should be referred to Acas (e.g. breaches of policies on expected behaviours, discrimination, victimisation or equality) – HSE is not the primary authority for these issues.

“Discrimination in relation to the protected characteristics of the Equality Act 2010 may constitute an offence and should be referred to the Equality and Human Rights Commission or Equality Advisory and Support Service.

“The Police deal with offences under criminal law including where there is physical violence or a breach of the Protection from Harassment Act.”

So, EHRC will never undertake preventive inspections to determine if employers are breaking the harassment law. And HSE, which undertakes thousands of preventive workplace inspections each year, may be there to identify risks but will walk on by.

These risks are not rare. Findings of a TUC survey published in May 2023 indicated three in five (58 per cent) women – and almost two-thirds (62 per cent) of women aged between 25 and 34 – say they have experienced sexual harassment, bullying or verbal abuse at work.

Conciliation Acas said its recent survey found 14 per cent of employers and 6 per cent of employees said they had witnessed sexual harassment in their workplace.

What is the Worker Protection Act?

The TUC is giving union reps pointers on duties and rights included in the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Act 2023 – the new law to protect workers from sexual harassment.

“After years of campaigning by the trade union movement and civil society to change the law so that employers, including trade unions, have to take a preventive approach to tackling workplace sexual harassment, the Worker Protection Act (otherwise known as the preventative duty) is finally on the statute books and coming into effect on 26 October 2024,” the TUC says.

“The new duty is an anticipatory duty, meaning that employers will need to take a proactive and preventative approach to protecting their employees from workplace sexual harassment. As so much of our research has shown, workplace sexual harassment is endemic, and while anyone can experience sexual harassment it is overwhelmingly women who are targeted.”

The TUC points to its own research which found half of all women have experienced workplace sexual harassment, rising to 7 in 10 for disabled women and LGBT+ workers, but four out of five do not report the harassment to their employer.

The union body says “many workers fear the repercussions of reporting sexual harassment and the impact it will have on them and their careers, there often aren’t many safe reporting routes for workers, and workplace power dynamics and factors such as insecure working arrangements often mean people feel they have little choice but to either put up with the harassment or leave their jobs.”

TUC says this is why the new duty “is an important move forward in tackling workplace sexual harassment – an absence of reporting does not mean there is an absence of sexual harassment or the cultures that enable it.

“And now rather than the onus being on victim-survivors to have to come forward before employers are obliged to act, the new duty means employers will have to proactively think about the potential risks in their organisations and take ‘reasonable steps’ to mitigate or minimise them, including risks posed by third party harassment (customers, clients, etc.)”

It highlights the “15 key risk factors” employers need to consider under the Worker Protection Act – all of which need to inform measure to reasonably mitigate those risks:

- power imbalances

- job insecurity, for example, use of zero hours contracts, agency staff or contractors

- lone working and night working

- out of hours working

- the presence of alcohol

- customer-facing duties

- particular events that raise tensions locally or nationally

- lack of diversity in the workforce, especially at a senior level

- workers being placed on secondment

- travel to different work locations

- working from home

- attendance at events outside of the usual working environment, for example, training, conferences or work-related social events

- socialising outside work

- social media contact between workers

- the workforce demographic, for example, the risk of sexual harassment may be higher in a predominantly male workforce.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) is the body responsible for enforcing the new duty, which can be enforced in two ways:

- An uplift in tribunal compensation (up to 25 per cent) where a tribunal finds in favour of the claimant bringing a sexual harassment case and finds the employer also failed to take reasonable preventive steps. However, an individual cannot take a tribunal claim against an employer for a breach of the preventive duty alone.

- Strategic enforcement powers for the EHRC to investigate suspected breaches of the duty. The EHRC will be able to investigate suspected breaches of the duty without an incident of sexual harassment having taken place.

TUC points reps to the EHRC technical guidance, which has been updated to reflect the new duty “and sets out very clear employer responsibilities and actions they can and should take, including risk assessments, having a workplace anti-sexual harassment policy, safe reporting routes, robust, fair investigation processes and training of all employees on workplace sexual harassment.”

UNION ACTION Risk assessments, consultation and negotiation are part of the trade union armoury against sexual harassment at work.

UNION ACTION Risk assessments, consultation and negotiation are part of the trade union armoury against sexual harassment at work.

But the union body adds the approach may fail without trade unions to ensure it works.

“Trade unions will have a vital role to play in ensuring that this new duty is effective and challenges sexual harassment in the workplace and the cultures that enable it,” it says.

“As we know, legislation can be a powerful tool but if it doesn’t translate into action, its impact is limited. That is why the TUC has worked with violence against women and girls and culture change experts to develop a toolkit for reps to take into their workplace and negotiate with employers to begin the necessary steps of building a preventative culture.

“We also have a key role in highlighting good and bad practice and supporting the EHRC to take enforcement action when employers fail to comply with the duty. Workplace reps are well placed to raise awareness of the new duty, bargain for better workplace practices and gather information on what is and isn’t working.

“Tackling workplace sexual harassment and building preventative cultures won’t be easy, but this new duty, which was hard won by trade unions and our partners, has the potential to make a significant and positive impact, making workplaces safer for everyone.”

It is a message reinforced by EHRC. It told Hazards: “Workers who experience sexual harassment can also seek assistance from trade unions, use their employer’s internal complaints procedures and make individual claims against employers and perpetrators of unlawful conduct to an Employment Tribunal.”

EHRC added: “Workers are also protected by equality law from victimisation, which is experiencing a detriment for making complaints of unlawful conduct in good faith.”

The new duty includes a definition of sexual harassment lifted from the Equality Act 2010, describing it as “unwanted conduct of a sexual nature” which has the purpose or effect of “violating [the worker’s] dignity” or “creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for [the worker].”

- TUC sexual harassment toolkit.

- Sexual harassment and harassment at work - technical guidance, EHRC, October 2024.

- 8-step guide for employers on sexual harassment in the work place, EHRC, October 2024.

STOP IT!

A new law gives women protection from harassment at work. It places for the first time a proactive duty on employers to prevent abuse. But Hazards editor Rory O’Neill warns the responsible regulator, EHRC, can’t undertake preventive inspections and HSE has stepped back, and now says it will do absolutely nothing to help the women at risk.

| Contents | |

| • | Introduction |

| • | Who’s looking? |

| • | Harassment hurts |

| • | What is the Worker Protection Act? |

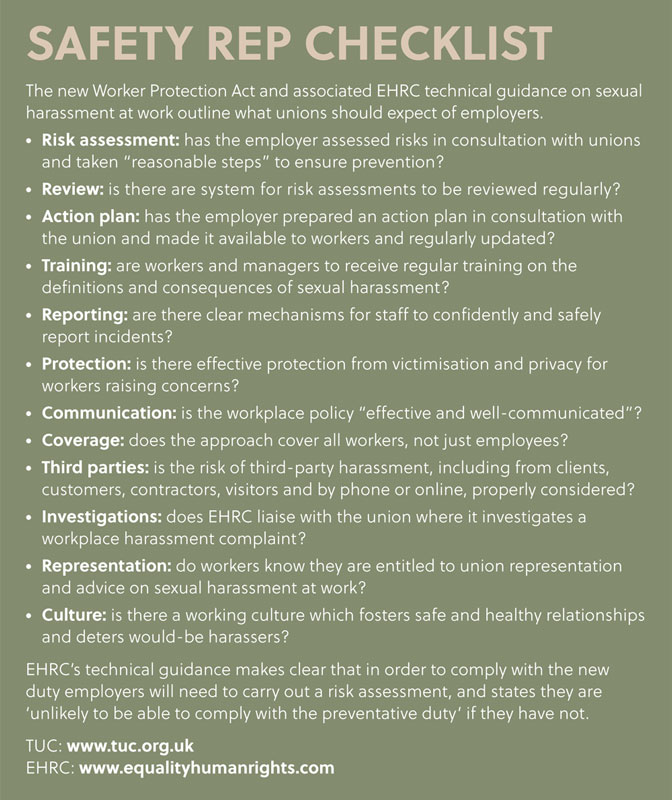

| • | Safety reps checklist |

| Hazards webpages | |

| • | Violence |