Abuse of power

Hazards issue 111, July-September 2010

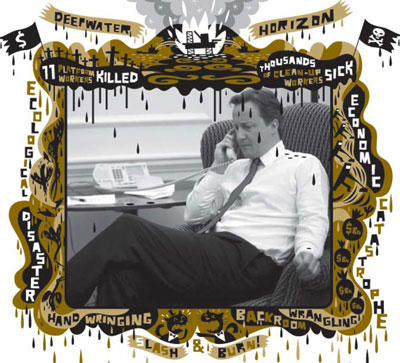

It’s a story that owes more to the ostrich than the oil covered pelican. The 14 June 2010 screen grab from the front page of the UK Prime Minister’s website shows David Cameron in a phone call to US President Barack Obama, discussing the 20 April Gulf of Mexico calamity – where oil spewed virtually unchecked until a cap on the Deepwater Horizon well offered some respite on 15 July.

REALITY GULF Prime Minister David Cameron tries to grease UK-US relations in a post-BP sliming phone call to US president Barack Obama. But the prime minister also wants to remove legal 'burdens' on business - like safety and environmental controls.

Cameron’s spokesperson commented: “The prime minister expressed his sadness at the ongoing human and environmental catastrophe in Louisiana,” adding: “President Obama said to the Prime Minister that his unequivocal view was that BP was a multinational global company and that frustrations about the oil spill had nothing to do with national identity. The Prime Minister stressed the economic importance of BP to the UK, US and other countries. The President made clear that he had no interest in undermining BP’s value.” [See: Plumbing the depths, pocketing the profits].

Observers increasingly accept the disaster was a product of inadequate regulation, oversight and enforcement. It caused incalculable economic and environmental damage, has strained relations between the US and the UK and has led for calls for directors of BP to face criminal charges. The company’s handling of the disaster at one point saw BP chief executive Tony Hayward, who will leave the top post on 1 October 2010, derided in the New York Daily News as “the most hated – and most clueless - man in America.” [See: Tony Hayward gets his life back].

There have been less celebrated casualties, notably the 11 workers who died when the rig exploded on 20 April. Since then many workers involved in the cleanup operation – possibly thousands – have fallen sick as a result of heat stroke, chemical exposures and other hazards.

PELICAN GRIEF The Gulf of Mexico oil spill has been dubbed the USA’s biggest offshore environmental disaster, and has also claimed the scalp of BP’s top boss, Tony Hayward.

Still, with the phone call over it was back to business as usual for the UK Prime Minister – pandering to the business lobby, with the next headline on the 10 Downing Street website: ‘PM announces review of health and safety laws’.

The review by Lord Young started out as a straight- forward pre-election Tory safety bashing initiative ordered by David Cameron. The then leader of the opposition called for an end to the UK’s “over the top” health and safety culture (Hazards 108).

But with Cameron now installed as prime minister, health and safety is facing a real and present danger, with the impact of Lord Young’s now government-sanctioned review likely to be amplified by other government action.

This includes the appointment of John Browne to oversee moves to make Whitehall “more businesslike.” As Tony Hayward’s predecessor at BP, Lord Browne was the architect of the much maligned cost-cutting strategy implicated in the Texas City refinery disaster, which killed 15, and a sequence of other safety and environmental crimes (Hazards 97). The scope of the peer’s shake-up of government will include all ministries, including those responsible for workplace safety and the energy industry.

Commenting on his appointment as a ‘lead non-executive director’ in government, Lord Browne said: “There is a great need for the best of the business community to be involved during these challenging times for the UK.”

Minister for the Cabinet Office, Francis Maude, said: “His experience will be a real benefit in our drive to make Whitehall work in a more businesslike manner and I am looking forward to working with him to implement our vital reform programme.”

Plans announced by chancellor George Osborne to cut departmental budgets across government, except health and aid, by at least 25 per cent and possibly up to 40 per cent will put extreme pressure on the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). For HSE’s parent department, the Department of Work and Pensions’ (DWP), the safety watchdog will be a soft target compared to any hope of quick savings by reducing the benefits bill at a time when numbers unemployed outstrip vacancies by five-to-one.

It’s a task made no easier by BP’s activities in the Gulf of Mexico. The company’s contribution to the Treasury’s coffers will be reduced by billions, as oil giant’s “expenses” dealing with the aftermath of the Gulf disaster are tax deductible.

[See: Who pays BP’s disaster bill? You will]

Deregulatory blitzkrieg

At the same time, the Coalition has embarked on a deregulatory blitzkrieg. A 1 July 2010 business department news release announced: “A tough new Cabinet committee with the job of reducing the heavy burden of red tape on business, which is chaired by business secretary Vince Cable.”

Cable commented: “For too long, there has been a misplaced notion that government’s job is to regulate. That is not the case. Regulation should be the last resort.” He added that the aim of the committee was “reducing the red tape that is strangling enterprise.” Deputy prime minister Nick Clegg also launched a ‘Your Freedom’ online “dialogue”, where the public can nominate “unnecessary” laws they would like axed, including a specific section on cutting business regulation.

Both business groups and the Conservative Party have said they consider health and safety regulation a “burden” which should be reduced.

WRONG CALL When BP demanded voluntary self-regulation of safety in the US, it got it. When it asked for official enforcement agencies to take a back seat in the Gulf of Mexico, it got it. It’s just Cameron didn’t get it – and straight after his call to President Obama to smooth out relations following the BP gusher in the Gulf, he announced plans to deregulate safety in the UK [See: Plumbing the depths, pocketing the profits].

But attacking safety regulation and enforcement is a departure for the Lib Dem side of the coalition government. In May 2003, Vince Cable, then the Lib Dem shadow trade secretary, criticised government plans to cut HSE’s budget because of the impact this will have on prosecution levels. He warned that was “critical that the HSE invest in a sufficient, effective, properly trained resource to investigate and prosecute where negligence has occurred.”

Since 2003, the resources available to HSE and the number of prosecutions taken have fallen dramatically (Hazards 110).

Hand-wringing by prime minister David Cameron over the “sadness” of the Gulf disaster is a seriously unsatisfactory alternative to protecting lives, livelihoods and the environment. To do that the government must behave responsibly, and that means more than just demanding responsibility from business.

It means less time spent appeasing regulation averse boardrooms and more time regulating them. What business calls “red tape” is for many workers their lifeline.

Removing or not enforcing legal protections makes a government an accessory to the crime.

Plumbing the depths, pocketing the profits

Producing oil may be a high risk business, particularly if you plumb unmanageable depths in the world’s oceans. But BP’s problem stems from its first priority: producing profits. Within a few short months of the Gulf of Mexico disaster, it looks like BP might soon be back to doing just that.

Before the Gulf oil spill BP was Britain's biggest company, with a stock market value of £121bn. But by mid-July shares had been hammered in the wake of the disaster, with more than £50bn wiped off the company's share value. But this was not because of concerns over the 11 dead in the original blast, or the prospect of multi-million dollar fines for safety and environmental crimes. It was because stock markets were unsure about just how much profit they could make while the oil continued to smear the US coast.

This was a firm that delivered over $2.6m profit per hour round the clock in the months prior to the Gulf disaster, despite having attracted the largest ever US safety fine on 30 October 2009 for its ongoing and deadly indifference to workplace hazards (Hazards 110). The share price bottomed on 29 June, at 302.9p.

After the markets heard a cap installed on 15 July appeared to be working, the BP share price turned sharply upwards. By 30 July 2010, three days after posting record losses, BP’s share price had recovered to 405.9p. This was way short of its recent high, around the 650p mark, but within the range of other non-disaster related price falls over the last three years, purely related to normal market fluctuations. By 4 August 2010, the day BP announced a “static kill” on the well had been successful, the BP share price, despite a major asset sale to cover the costs of the disaster, had recovered to 421.65p. The company, it appeared, may have weathered the storm.

“The costs and charges involved in meeting our commitments in responding to the Gulf of Mexico oil spill are very significant and this $17 billion reported loss reflects that,” said out-going chief executive Tony Hayward, announcing BP’s 2010 second quarter results on 27 July. “However outside the Gulf it is very encouraging that BP’s global business has delivered another strong underlying performance, which means that the company is in robust shape to meet its responsibilities in dealing with the human tragedy and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Prime minister David Cameron’s earnest representations to Barack Obama – by phone on 12 June 2010 and in person, during his 19-20 July 2010 visit to the White House - were about the welfare of the BP, a private corporation. The personal ‘human tragedy’ – like the estimated 50,000 occupational injury and disease deaths each year in the UK – was the result of the type of inadequate regulation of businesses lobbied for by BP and that Cameron’s government is keen to extend.

BP’s Tony Hayward gets his life back

He’s the casualty of the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe least likely to elicit sympathy. BP announced on 27 July that beleaguered chief executive Tony Hayward is to go “by mutual agreement” on 1 October. He will be replaced in the top job by Bob Dudley, whose American accent is expected to be less galling to US ears.

Hayward – whose high profile gaffes included telling CNN, as the oil lapped the Gulf coast, “I’d like my life back” – will at 53 qualify immediately for a £600,000 annual pension, a £1.045m pay off in lieu of notice and a multi-million portfolio of company shares. He will be given a place on the board of BP’s Russian offshoot as a consolation prize and will retain his seat on BP’s global board until 30 November.

Commenting on the decision to step down, Hayward said: “The Gulf of Mexico explosion was a terrible tragedy for which - as the man in charge of BP when it happened - I will always feel a deep responsibility, regardless of where blame is ultimately found to lie.” He added: “We have now capped the oil flow and we are doing everything within our power to clean up the spill and to make restitution to everyone with legitimate claims.”

This includes less celebrated casualties of the Deepwater Horizon explosion, notably the 11 rig workers who died, whose dependants are between them unlikely to receive “legitimate” recompense totalling anything like the lifetime supply of BP cash Hayward is to enjoy. His pension pot already is valued at about £11m.

When Hayward took over the helm in 2007, he told journalists his number one task was to focus “laser-like” on safety and reliability. The company laid a marker on its response to possible criminal action on 27 July – the same day it announced Hayward’s departure - saying BP did not believe it was “grossly negligent” in regard to the oil disaster.

BP hopes the departure of Hayward will be the beginning of the end for its Gulf of Mexico woes, and the reputational harm that came with it. However, just three years ago when Hayward took over the helm, BP was also hoping a change of leadership would create clear blue water between the firm and other safety and environmental blunders, notably the 2005 Texas City refinery explosion that killed 15 on the watch of Hayward’s cost-cutting predecessor Lord John Browne.

Hazards green jobs blog • BP news release • Hazards BP webpages.

Who pays BP’s disaster bill? You will

If you thought the multi-billion dollar costs of destroying refineries and oil rigs (and killing workers, ruining livelihoods and wrecking the environment in the process), might have a chastening effect on BP, you might need to think again. BP is forecast to pay about $10bn less tax over the next four years as it meets the costs of its huge oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, hitting the revenues of Britain and the US, who both receive hundreds of millions in tax from the company each year.

Because the laws of both the US and the UK allow companies to deduct from their taxes what are called “business expenses” – and that includes cleaning up messes caused by doing business the wrong way, cutting corners and violating safety and environmental laws – BP will transfer about a third of all their costs of dealing with the Gulf of Mexico oil disaster away from the company and directly onto the taxpayers of the US and the UK by deducting all these costs from their taxable profits. Of its principal expected liabilities, only the fines that might be imposed by the US authorities would definitely not be tax-deductible.

BP’s bad behaviour is not restricted to the US. The troubled oil giant has been caught breaking health and safety regulations 54 times over the past five years in the UK, according to Health and Safety Executive (HSE) records. HSE took action against BP repeatedly after identifying a series of maintenance and operating lapses which put workers and the environment at risk from major leaks, fires and accidents in its in the London-based multinational’s onshore and offshore UK operations.

As a result HSE has served BP companies with 21 legal enforcement notices since 2006, requiring lax and dangerous practices to be improved. The company, however, has not been prosecuted by the watchdog since 2005. Enforcement notices can only be imposed where there has been a criminal breach, but the company escapes a legal penalty or court appearance.

One way or another BP appears insulated from the real consequences and costs of its criminal behaviour. This is one reason why jail terms on the oil giant’s directors for their safety crimes, including chief executive Tony Hayward, might have a more salutary effect on BP’s boardroom behaviour. It would certainly be a rare bonus for the rest of us.

Abuse of power

Contents

• Introduction

• Deregulatory Blitzkrieg

Extra features

Plumbing the depths, pocketing

the profits more

BP’s Tony Hayward gets his life back more

Who pays BP’s disaster bill? You will more

Hazards webpages

Vote to die • Deadly business • Hazards on BP