The real job killers

Hazards issue 113, January-March 2011

Wherever you go, business lobby groups are trotting out cookie-cutter reports claiming businesses are folding, jobs are being lost, and the economy is being devastated. And the cause? The burden of regulation, with health and safety rules always targeted as a top “job killer”.

‘Don’t base policy on deadly lies’, a November 2010 online report from Hazards, notes: “The perpetual belly-aching about workplace regulations is packaged the same both sides of the Atlantic, and contains the same claims about the dire impact of employment and safety regulations on business and the economy. It’s a clarion call that gets heard by frequently uncritical government agencies.”

DEADLY SERIOUS Every year, tens of thousands of families in the UK lose someone to a work-related injury or disease. There’s nothing inevitable about this. What is inevitable is that diluting safety laws and hobbling the official safety watchdog – both policies of the UK government – will mean more suffering and more deaths. [see: Is HSE finished?: Government cuts HSE’s throat and ties its hands]

The report points to the British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) annual off-with-their-regs manifesto, the ‘Business burdens’ report (Hazards 111). Every year this gives health and safety top billing. The 2010 edition, published in May 2010, points to the “burdens” of rules providing workers with protection from hazards including explosives, chemicals, work at height, biocidal products, vibration and noise.

BCC estimates these safety regulations lead to a combined recurring annual cost to business of £374 million. The cumulative cost since 1998 tots up to £2.963 billion.

It sounds like a lot. But BCC has not only got its sums wrong, its tried, with some success, to hookwink the government, the media and the public at large with deadly omissions and gobsmacking lies.

It will cost you

The Hazards ‘Deadly lies’ report notes: “BCC relegates to the technical notes an admission that the costs to business identified ‘are net of the benefits that accrue to business.’ And it discounts entirely the cost paid by the victims of slack health and safety standards. This human price out-strips the business cost several times over.”

A May 2006 UK government regulatory impact assessment put the total cost of non-asbestos occupational cancer deaths each year, at 2004 prices, at between £3bn and £12.3bn. In just one year, just some of the occupational cancers carry a cash cost between eight and 33 times even BCC’s lop-sided and inflated £374 million estimate of the annual cost of safety regulations.

Add in the cost of work-related asbestos cancers, other occupational diseases and work injuries, and it becomes apparent that health and safety regulation and enforcement already delivers a colossal cost saving across the economy. But it could save a lot more. Regulating safety is the ultimate austerity measure – it not only saves money, it saves lives (Hazards 112).

Why business doesn’t care

Two factors explain the business lobby’s reluctance to concede safety laws are good for all of us. Firstly, profits are the key performance measure at company annual general meetings (Hazards 110). Secondly, analyses from the UK, US, Australia and elsewhere establish the total cost of neglecting workplace health and safety may be astronomically high, but it barely falls at all on business (Hazards 106) – the one party with something to gain from cost- and corner-cutting at the expense of safety.

A 2008 analysis by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) concluded: “Although the costs of workplace injuries and work-related ill health are attributable to the activities of the business… the bulk of these costs fell ‘externally’ on individuals and society.” HSE estimates less than a quarter of the cost of work-related injuries and ill-health is borne by employers. And some recent evidence suggests this “cost-shifting” by business could be costing the rest of us considerably more.

A November 2010 UK study, published in the journal Thorax, concluded about 49 per cent of the lifetime costs of occupational asthma are borne by the individual, 48 per cent by the state and just 3 per cent by the employer.

Corpses and casualties

This work-related toll is not yesterday’s problem. Figures published by HSE in October 2010 showed the number of people harmed by their jobs had increased (Hazards 112).

In the year from April 2009 to March 2010, 1.3 million current workers reported they were suffering from an illness caused or made worse by their work, up from 1.2 million in 2008/09. HSE said 555,000 of these cases were new illnesses occurring in-year, a 4,000 increase on the number of new illnesses recorded the previous year. A further 800,000 former workers claim they are still suffering from an illness caused or made worse by work.

But these official figures record only a small fraction of the harm caused by work. Studies suggest up to 20 per cent of the UK’s biggest killers, including heart disease, cancer and chronic respiratory disease, are caused by work, suggesting an annual work-related death toll in excess of 50,000 and a working wounded list of several million (Hazards 92).

Absent from the business costs ledger is this coughing, bleeding, crying and dying that results from the criminal neglect of worker safety. And that’s no accident. Framing health and safety protections as a job killer, rather than their absence as a killer full-stop, keeps the real costs – people who get sick and die – safely out of the argument.

Britain waives the rules

The rigged business costings get repeated as fact and form a core part of the deregulatory arguments that shape governmental policy. But the business lobby is complaining about a regulatory burden to business competitiveness that does not in fact exist. Out of all the OECD countries, the lowest levels of legal employment protection are found in the USA, Canada and Britain.

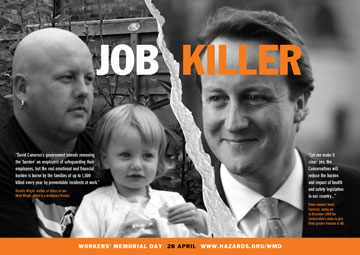

The UK government’s “employer’s charter”, launched by prime minister David Cameron on 27 January 2011, is set to consolidate Britain’s place in the workplace decency hall of shame. It spells out the gaping holes in the protection provided by UK employment law. But it’s a charter that omits any mention of the moral, legal or business arguments for being a good employer. Decency doesn’t register on the chart.

If the objective is to make work safer and reduce the related human and economic costs – rather than pander to the business lobby so it will pad out the government’s election war chest - then regulation and enforcement should be the preferred option.

Professor Phil James of Middlesex University Business School, in research for HSE published in 2005, concluded “existing evidence suggests that legal regulations and their enforcement constitute a key, and perhaps the most important, driver of director actions in respect of health and safety at work.” The academic literature is dominated by studies showing three factors are key to making work safer: decent regulations; a meaningful threat of enforcement backed up by punitive penalties; and genuine worker involvement (Hazards 111).

Bankrupt arguments

It’s not just that the business argument concentrates solely on the costs rather than the benefits of health and safety regulations, both business and regulators are inclined to over-estimate the costs and the consequences.

In ‘The going out of business myth’, US group OMB Watch cites a succession of dire warnings about the cost implications of the introduction of workplace safety regulations covering asbestos, cotton dust, vinyl chloride and other highly hazardous substances – many of which turned out to have zero or minimal costs.

It notes: “The public needs regulatory safeguards to protect our health, safety, environment, civil rights, and welfare. Corporate special interests, however, have an interest in avoiding spending a single dime to improve their destructive behaviour. Again and again, when new regulatory protections have been proposed, corporate lobbyists have argued that business would be bankrupted and forced to go out of business. Again and again, they have been proven wrong.”

‘Good rules: Ten stories of successful regulation’, a 2011 report from the New York-based think tank Demos, highlights the business lobby’s scaremongering on vinyl chloride.

“In 1974, the newly established Occupational Safety and Health Administration announced a set of rules to reduce worker and public exposure to vinyl and polyvinyl chloride – two resins identified as major contributing factors to liver cancer. The affected manufacturers claimed at the time that they would have to spend a combined $90 billion, and terminate thousands of workers, in order to comply. Toting up the results a decade later, the Reagan administration found a significant decline in deaths from liver cancer, achieved at a cost of $300 million (1/3 of 1 per cent of the forecast) and zero jobs.”

The Demos report concludes: “History tells us to have confidence, and, moreover, to raise our sights. Good Rules (as these stories show) are not a substitute for competition, innovation, or market forces; they merely help channel the forces of the market in more positive directions. The ban on vinyl chloride (like similar phase-outs of hydro-fluorocarbons and other dangerous chemicals) stimulated the development of more efficient and safer technologies.”

It’s a message repeated in ‘Cry wolf – predicted costs by industry in the face of new regulations’, an April 2004 report from the International Chemical Secretariat (ChemSec). This found both industry, in resisting regulation, and regulators, through under-estimating the potential for beneficial innovation, over-estimated costs.

It noted “general and vague” business lobby statements “range from claims that regulation will cause the downfall of whole industry sectors to the oft-repeated story of how regulation would drive one particular (usually imaginary) small or medium-sized enterprise out of business.”

It’s a toxic, but very deliberate, combination of bad science and bad sums (Hazards 103).

ChemSec found industry’s smoke and mirrors “seem to exert an unduly large influence as they are frequently quoted by politicians and included in official background papers.” It concluded: “The cases studied show that cost estimates from specific interest groups within industry generally overestimates predicted compliance costs and underestimates innovation potential,” with the tendency also, although to a lesser extent, infecting regulators.

Courting disaster

It’s not that governments don’t know regulation-lite approaches have deadly consequences.

A lack of oversight by official agencies has been implicated in a sequence of occupational and environmental catastrophes, from the Gulf of Mexico disaster in 2010 to the cancerous clean rooms of microelectronics manufacturers (Hazards 111). And studies by official agencies in both the UK and the US have shown businesses take dangerous liberties when left to their own devices, and are far more likely to do the responsible thing when facing a realistic prospect of inspection, enforcement and criminal penalties.

In between disasters, governments forget the evidence and gloss over the crimes and revert back to blind trust and business-friendly talk of health and safety deregulation. Only when the deaths come in a rush and industry’s safety peccadilloes are in the media spotlight, is common sense briefly restored and talk of responsible inspection and enforcement regimes preferred to blind trust. But responsible enforcement trumps blind trust all the time, not just when the media is showing an interest.

Business over-estimates costs and ignores benefits with a purpose. It doesn’t want regulations and it doesn’t want enforcement.

In the deadly scheme of things, lying so they can leave their workforce in the firing line is the least of their money-motivated crimes. Somewhere down the line, people die when regulatory protection is removed. That’s the ultimate capital crime.

Key references

Don’t base policy on deadly lies, Hazards online report, November 2010. Dangerous li(v)es, Hazards, November 2010.

The costs to employers in Britain of workplace injuries and work-related ill health in 2005/06, HSE Discussion Paper Series, No. 002, September 2008 [pdf]. HSE health and safety economics webpages.

Economic Analysis Unit (EAU) appraisal values, HSE, July 2008 [pdf].

www.hse.gov.uk/economics

Jon Ayres and others. Costs of occupational asthma in the UK, Thorax, Online First, 25 November 2010. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136762 [abstract].

HSE news release and report, Statistics 2009/10 [pdf].

Employer’s charter, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, January 2011 [pdf].

Directors’ responsibilities for health and safety: the findings of two peer reviews of published research, HSE research report RR451, HSE, 2005 [pdf].

The going-out-of-business myth, OMB Watch, July 2005 [pdf].

Good rules: Ten stories of successful regulation, Demos, 2011.

Cry wolf – predicted costs by industry in the face of new regulations, International Chemical Secretariat (ChemSec), April 2004.

The real job killers

Contents

• Introduction

• It will cost you

• Why business doesn’t care

• Corpses and casualties

• Britain waives the rules

• Bankrupt arguments

• Courting disaster

• Key references

Hazards webpages

Vote to die • Deadly business