You are on the edge. The targets are tight. You hit one, they raise it. You miss one, you are in trouble. It’s all about the product. Get the job out, or get out. The boss doesn’t care. But then the boss is a computer programme.

It might sound like a dystopian future workplace but it is happening today, breaking bodies and breaking hearts. Excessive pace of work is becoming the norm – driven by performance management systems, reward systems and piece work, job insecurity and old fashioned management because-I-say-so.

But Artificial Intelligence (AI) has ratcheted up the pressure several notches. ‘Intensification of work’ is the desired anxiety-inducing consequence, and workplace health and safety law is not keeping up.

PACE OFF In September 2021, California introduced into law a first-of-its-kind bill aimed at empowering workers at companies using algorithms to enforce work quotas in warehouses – often pushing them to skip breaks and work unsafely in order to “make rate.” more

Management practices at Amazon, which said its UK workforce would rise to 55,000 by the end of 2021, are proving a gamechanger across the economy.

You can forget the boardroom cliche ‘our workers are our biggest asset’. In July 2021 internal Amazon documents emerged revealing executives at the world’s largest retailer “closely track” and set goals for a metric called the “unregretted attrition rate” – the percentage of workers the company is happy to see leave every year.

Australian researchers from Monash, Melbourne and RMIT universities studying Amazon’s practices found it operated a system of “automated precarity,” resulting in “burnout by design.”

University of Toronto academic Alessandro Delfanti described Amazon’s use of algorithms to organise work as “augmented despotism”, driving workers to leave their jobs at the point where their bodies simply cannot handle the strain any longer.

Amazon’s disposable workers, a March 2020 report from the US National Employment Law Project (NELP) quantified the attrition effect, finding: “The average turnover rate for warehouse workers in counties with Amazon fulfilment centres was 100.9 per cent in 2017, the latest year for which data are available.” NELP concluded: “Amazon relies on an extreme high-churn model, continually replacing workers in order to sustain dangerous and gruelling work pace demands.”

Most workers at Amazon are contract labour, not directly employed (Hazards 143). These unsecure workers report routinely that they are required to work at an accelerated pace for incredibly long hours.

It’s not AI OK

The 2020 NELP report cites data from the company’s own records that reveal ‘stunningly high injury rates’ in the retailer’s US warehouses.

TOO MUCH A Health and Safety Executive (HSE) December 2021 report on work-related stress, anxiety and depression noted its analysis of causes conducted pre-pandemic found “workload, in particular tight deadlines, too much work or too much pressure or responsibility” topped the list. Amazon’s big sales events create the perfect environment for these conditions, creating high accident and attrition rates.

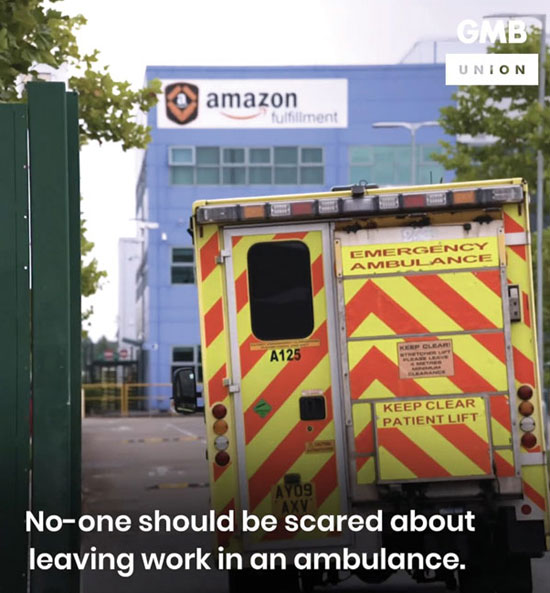

In the UK, research by the union GMB published in November 2021 revealed ambulance call-outs rise sharply in the run up to big sales events like November’s ‘Black Friday’ and Christmas, peaking as the deadline looms.

Amazon points to its WorkingWell programme and AmaZen ‘mindful’ meditation booths (right) as evidence it cares for its staff (Hazards 154). But others have described the warehouse pods as “crying booths.”

Upping targets and demanding more with menaces have always been part of the bad management playbook. But turning the screw has been turned into an inhumane – unhuman – science by AI. And it is not just Amazon at it.

We’re all Amazon now

DRIVING IMPROVEMENTS More than 5,000 Korean truck drivers rallied in front of the transport ministry in Seoul on 29 October 2021 demanding an expansion of the country’s ‘Safe Rates’ system. It marked the conclusion of a ‘Week of action for decent work and safety in road transport’ organised by the global transport workers’ union federation ITF that saw workers around the world take to the streets. ITF general secretary Stephen Cotton said the solution to the road transport crisis is “called decent work and safe rates and it starts with accountability from the companies at the top of supply chains.” More • www.itfglobal.org

The New Frontier: Artificial Intelligence at Work, a November 2021 report from the UK government’s all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on the future of work noted: “Pervasive monitoring and target-setting technologies, in particular, are associated with pronounced negative impacts on mental and physical wellbeing as workers experience the extreme pressure of constant, real-time micro-management and automated assessment.”

The Amazonian Era, a May 2021 report from the Institute for the Future of Work, found Amazon-style Artificial Intelligence systems “are designed to drive the completion of more tasks in less time, intensifying work.”

Workers from across a range of industries told the Institute that AI target-setting produced high levels of anxiety. Its conclusions are based on interviews with managers and workers from across the retail, logistics, manufacturing and food processing sectors.

PAYING THE PRICE A MakeAmazonPay campaign saw activities worldwide on 26 November 2021. Sharan Burrow, general secretary of the global union ITUC, said: “The ITUC categorically backs this call to make Amazon pay and make Amazon a better company that respects, listens to and values the working people behind its success.” The Make Amazon Pay coalition includes the ITUC and the global commerce union UNI and

over 70 trade unions, civil society organisations, environ- mentalists and tax watchdogs. www.MakeAmazonPay.com

“Standards set by algorithms are then used to evaluate and manage performance, incentivise or penalise workers, and grant or deny access to work,” it reported.

Some working drivers said they were forced to cut corners because of time constraints and manufacturing workers said constant logging of their activities on shifts led to more intensive work.

To address gaps in current legal protections, the report concluded: “Government should initiate an Accountability for Algorithms Act in the public interest which will require early algorithmic impact assessment and adjustment when adverse impacts are identified.

“Algorithmic impact assessment should extend to equality impacts and the physical, mental and financial risks of labour intensification.”

Other studies of workers in call centres, retail, transport and logistics and across the public and private sectors reveal a remorseless demand for increased productivity.

Attrition is part of the model. If you can’t keep up, you can’t keep your job.

Pace off face off

In the absence of legal protections, unions have harnessed technology to expose unreasonable demands at work.

The WeClock self-tracking app, produced with the global union UNI, describes itself as a ‘workplace reality check’ that allows a worker to collect data about their working life to challenge unrealistic demands, the ‘constant on’ culture and a lack of time off and breaks.

The app development team note: “Researchers from Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, world-leading digital experts and trade union organisers from across the world have supported and advised us along the way.”

Questions the developers say the app can address include “are work demands impacting health? Find out if productivity demands are causing physical, mental or personal strain.”

It adds: “WeClock equips workers with a way to quantify their workday. Introduce it to your members to ignite a conversation and spur collective action.”

Examples of the problems the resource can address include “inhumane expectations of worker ‘efficiency’” in warehouse workers, long hours and lack of breaks in gig workers and security guards, “unrealistic routing” for delivery workers and “long shifts on their feet and unpaid extra work” for retail workers.

Others in a long list of jobs where workers could benefit include waitresses facing “high productivity demands and long hours and skipped breaks”, office workers experiencing “long sedentary days at their desk” and call centre workers faced with a “stressful job with limited movement.”

There should be law

There are signs some lawmakers have also had enough. But the positive moves are not in the UK. In September 2021, California introduced a first-of-its-kind bill aimed at empowering workers at companies using algorithms to enforce work quotas in warehouses – often pushing them to skip breaks and work unsafely in order to “make rate.”

Announcing the new law, Assembly Bill 701 (AB701), California governor Gavin Newsom said: “We cannot allow corporations to put profit over people. The hardworking warehouse employees who have helped sustain us during these unprecedented times should not have to risk injury or face punishment as a result of exploitative quotas that violate basic health and safety.” He added: “I’m proud to sign this legislation giving them the dignity, respect and safety they deserve and advancing California’s leadership at the forefront of workplace safety.”

AB701 requires companies to disclose to the authorities and to their employees the quotas that are used to track productivity, prohibits penalties for “time off-task,” and bars companies from retaliating against workers who complain about the metrics used.

Under the new rules, “quota” is defined as a work standard under which an employee is assigned or required to perform at a specified productivity speed, or perform a quantified number of tasks, or to handle or produce a quantified amount of material, within a defined time period and under which the employee may suffer an adverse employment action if they fail to complete the performance standard.

The law notes that any current or former employee who “believes that meeting a quota caused a violation of their right to a meal or rest period or required them to violate any occupational health and safety laws” can demand information relating to “the employee’s own personal work speed data.” After a worker complaint, the relevant authorities can “request or subpoena the records of warehouse distribution center quotas and employee work speed data.”

This includes “an individual employee’s performance of a quota, including, but not limited to, quantities of tasks performed, quantities of items or materials handled or produced, rates or speeds of tasks performed, measurements or metrics of employee performance in relation to a quota, and time categorised as performing tasks or not performing tasks.”

Laws dealing explicitly with pace of work are unusual and contentious, challenging company production goals. In 2021, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) supported line speed limits in chicken and hog processing. Unions had consistently pressed for the protections for workers who were suffering high rates of serious cut and ergonomic injuries. The industry lobby has just as vocally opposed the measures.

In Finland, safety inspectors employ the Valmeri questionnaire when inspecting workplaces, which includes a five point rating, where workers are asked to rank their ‘psychosocial workload’, from ‘totally agree’ to ‘totally disagree’ for nine categories. These include ‘I usually have enough time to perform my work properly and safely’ and ‘I am not too often forced to work to the limits of my abilities.’ Another reads ‘Tasks, objectives and how to achieve them are discussed sufficiently at my workplace.’

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive’s Management Standards cover six categories: demands, control, support, relationships, role and change. But to find any explicit pointers on pace of work, you have to burrow deeper.

The linked HSE workbook, Tackling work-related stress using the Management Standards approach, identifies pace at work as one of the relevant concerns, suggesting managers in cooperation with workers should check factors including “the way work is done, the pace of work, or working conditions” which may cause problems. In a “do’s and ‘don’ts” appendix, HSE tells firms to “allow staff some control over the pace of their work,” and “allow and encourage staff to participate in decision-making, especially where it affects them, eg. those about the way they work.”

Quoting the standards may be enough.

But standing together against unsustainable work rates is a much safer bet.

Resources

| • | www.warehouseworkers.org |

| • | When AI is the boss: An introduction for union reps, TUC, December 2021. |

| • | World Health Organisation (WHO) Q&A on stress at work. |

| • | HSE Management Standards and related workbook, Tackling work-related stress using the Management Standards approach. |

| • | Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain, HSE, 16 December 2021. |

| • | Health and safety at work: Summary statistics for Great Britain 2021, HSE, 2021. |

Amazon hospitalisations spike as it piles on the pressure

Ambulance callouts for injuries and other health concerns at Amazon warehouses surged almost 50 per cent in the run up to Black Friday on 26 November 2021, research by GMB has revealed. The union used freedom of information requests to obtain monthly data from four ambulance trusts that cover major Amazon sites. Its analysis shows that, over a five-year period, November was the worst month for ambulance callouts.

Black Friday – which follows the US Thanksgiving holiday on the last Thursday in November – saw demand for ambulances grew by 46 per cent between October and November 2021 alone as the company piled on the pressure to fulfil orders. GMB is calling on the company to address its problematic health and safety record.

GMB national officer Mick Rix commenting: “While most people enjoy their Black Friday bargains, Amazon workers are being pushed beyond the limits of human endurance. Each year, ambulance call outs to Amazon sites rocket as workers desperately race to hit their crushing targets.”

He added: “The horrific evidence is here in black and white – ambulance crews are called out to Amazon sites almost 50 per cent more in November. Workers are breaking bones, being left in pain at the end of a shift and getting barred from work for raising Covid complaints. Amazon can’t deny it any longer. GMB calls on the Health and Safety Executive to investigate these inhumane working practices.”

Rix concluded: “This company is a pandemic profiteer and can afford to do better – it’s time for Amazon to sit down with their workers’ union GMB and make Amazon a great, safe place to work.”

The GMB’s findings are based on data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act from NHS ambulance trusts covering the North West, the East Midlands, London and Wales.

E-commerce and Christmas have become so entwined for Amazon its global logistics chief Dave Clark referred to the company’s warehouses as “Santa’s workshops”.

Road transport workers in global safety campaign

A ‘Week of action for decent work and safety in road transport’ organised by the global transport workers’ union federation ITF has seen workers from the sector take to the streets to press their demands for ‘safe rates’ of pay and decent work. The event, which ran from 21 to 28 October 2021, culminated with a major rally in Seoul.

More than five thousand Korean truck drivers – members of KPTU-TruckSol, the Cargo Truckers’ Solidarity Division of the Korean Public Service and Transport Workers’ Union – rallied in front of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport in Seoul demanding the preservation and expansion of the Korean ‘Safe Rates’ system. ITF said many road transport unions also used the action week to make demands of their own governments, employers, and client companies.

In Australia, it saw the climax of a month of rolling strikes with 24-hour work stoppages by StarTrack and FedEx workers. The Transport Workers’ Union of Australia (TWU) is calling for job security guarantees and federal action on safe and fair minimum standards.

“The week of action has been successful in making governments and corporations around the world know that we have a solution to the crisis in road transport,” said ITF general secretary Stephen Cotton. “It is called decent work and safe rates and it starts with accountability from the companies at the top of supply chains. This solution has already been endorsed by the ILO. It’s time for governments, employers and clients to come to the table with unions and put this solution into practice.”

A three-day strike from 25 to 27 November 2021 was called by KPTU-TruckSol to increased pressure on the government to extend and strengthen South Korea’s Safe Rates system which despite opposition is scheduled to be phased out at the end of 2022. Safe Rates sets minimum rates of pay and related working conditions for owner-operator truck drivers across the road transport sector.

On the final day of the action, around 8,000 truck drivers converged in front of the National Assembly building in Seoul. The protesters secured the street and carried out a strike rally despite authorities denying a permit for the rally resulting in a face-off with thousands of police officers.

Addressing the crowd, KPTU-TruckSol President Bogju Lee called on the Moon Jae-in administration and lawmakers to come forward and pass new legislation to strengthen drivers’ rights and make Safe Rates permanent. “The reason so many non-members are participating in this strike is because our demands for legal reform represent the desperate cry of all truck drivers,” said Bogju Lee.

“This strike is about road safety and the safety of the travelling public. In the last two days, we have demonstrated our ability to completely paralyse the country should the government not listen to our demands and force us to take further strike action.”

KPTU-TruckSol has promised to take unlimited strike action should their demands not be met.

| • | ITF safe rates campaign webpages. |

Back to main story • Top of the page

Fast and furious

You work hard, you hit targets, you survive another day. But then the targets ratchet up, enforced by AI systems, modern performance management or old-fashioned bosses just turning the screw. Hazards editor Rory O’Neill warns workers have good reason to be angry about the fast-paced disposable worker grind.

| Contents | |

| • | Introduction |

| • | It’s not AI OK |

| • | We’re all Amazon now |

| • | Pace off face off |

| • | There should be law |

| • | Resources |

| Related stories | |

| • | Amazon hospitalisations spike as it piles on the pressure |

| • | Road transport workers in global safety campaign |

| Hazards webpages | |

| • | Hazards news |

| • | Work and health |

| • | Stress |

| • | Work suicide |